Software At Its Core: Tradeoffs, Opinions and Chaos

To get one thing, you have to lose another.

The above is a line that (or something similar to it) you would often find in many movies; an icing on the cake if that movie is an action movie and the line comes from the mouth of the protagonist, who’s at a crossroads between what they could lose versus what they could gain and the stakes are high.

Not in my entire life would I have ever associated the line with a domain the public doesn’t associate with action heroes or big decisions; yet, it is this domain that sees the most application in choosing between one or the other. The domain I’m referring to is, of course, Software Engineering.

Just to give you some idea about the extent of how often there are crossroads in software, just to get a simple website with a form, you have an infinite number of ways to get started and ship. Every step of the way you’re weighing the benefits and making a decision about which one to go forward with.

For decisions, there are opinions

Every day, a software engineer would make a lot of decisions, especially if the project is new. It is also at the beginning of the project that decisions tend to make a huge impact on the direction and effort required for the project in the long run. Just ask someone who chose a shiny new database to work with.

Decisions about tech stacks, libraries and frameworks define how your app’s code is constructed (Read: Structured + Written). Your code has to work around the limitations of your libraries, frameworks and databases, and at the core, the limitations of the programming language (And no, different programming languages ARE better at different things than others. Try writing a web server in C++, heck try writing a simple webpage in Brainfuck and you’ll know what I am talking about)

Given you have to construct your code around the constraints of your decisions, the decisions tend to be made as a result of opinions. Those opinions might be from people who have worked on similar projects or tech stacks before or from previous experiences (Read: Burns from previous projects).

Even something like how you structure your file system, and where you keep your helper functions are all opinions, everyone has a different one and something so seemingly simple can become either a significant hassle or a blessing in the long run.

When to choose a NoSQL database versus a SQL database? If NoSQL then MongoDB or Firestore? If SQL then Postgres or MySQL? Which web server to use? Should it be a native desktop app? If so, Electron with a web app shell inside or native apps with C++? Do we need a mobile app? If yes, then Kotlin or Java or a hybrid app written with React Native or Flutter? Would I need a message queue or not?

If you’ve been building projects for some time, you will know that most of the questions above do not have clear choices. Whether you need a native desktop app or a mobile app is simple to guess, you determine it using your target audience, a ride-hailing service would not need a native desktop app (Of course). But what you build the service with is entirely up to you.

You can build an amazing web app with a single-threaded Node.js server, and you can create a poorly performing web app with Go. You could scale to millions with a SQL database and at the same time hit a block with a NoSQL database. It’s a lot about knowing the tools you’re using.

With decisions, come tradeoffs

A big element of the outcomes is the tradeoffs or limitations that come with the decisions you would take about variable elements of your architecture.

Everything in software is pretty much a tradeoff, you choose one programming language to gain an edge on one feature but in turn, end up compromising on aspects the programming language might not be good at.

You choose databases that have extremely fast read times but trade-off speed when writing data. Building a distributed system? Good luck working with the constraints of CAP theorem.

One thing to note is that you would often not see tradeoffs or limitations of your choices until the decisions have already been a big influence in your application.

Tradeoffs usually aren’t a problem, in fact, they are a given, this is where the “To get something, you need to lose something” kicks in and it becomes about choosing the “least damaging tradeoff” instead of “no tradeoffs”.

As the saying goes:

You can’t have everything

Combine decisions and tradeoffs with requirements, and you get chaos

Now that we have put together all the decisions we made into our tech stack, and embraced the tradeoffs that come with them; we still have a few things left to take care of, end-user requirements.

They are inevitable. Picture this, you’re asked to build a ticketing system, in an ideal world, the requirements of the end-users at a particular point in time would be very clear in the form of user stories and potential future requirements are listed down to the best possible extent. But we don’t live in an ideal world, many-a-times the project might be an MVP to gauge what works and what doesn’t, and hence the requirements are only clear to the MVP’s standard, what is required “right now” and worse yet “by this Friday”.

Now there are a few cases here:

- You’re building the feature from scratch, i.e: It’s a new project.

- You’re building the feature as an extension of a project that’s already built.

In the first case, you can surely make decisions about the most appropriate tech stack and patterns you want to use to ship the feature out. But in the case of an existing project, it could be a big hassle if the feature is relatively disconnected in terms of requirements from the existing project (Trust me, it happens, a company is free to venture into unrelated avenues and you, the engineer, has to ensure that the part of the website for that new venture is up and running along with the existing website by Friday evening).

When you built the original project you might have gauged a NoSQL database might be the best choice, and it has been working great ever since. However, for this new feature, a SQL database might be best, you have two choices (Both difficult) in situations like these:

- Choose a different stack and add complexity at the tech stack level (Multiple databases etc).

- Try extending the same stack with an unrelated and adding complexity at the code level (Things like trying SQL join-like capabilities with your existing NoSQL database).

Most of the time, you would go ahead with the second approach, purely because it’s faster to do and it keeps your tech stack simple. This, however, adds a lot of complexity to your codebase, simply because something that isn’t supposed to be there, is.

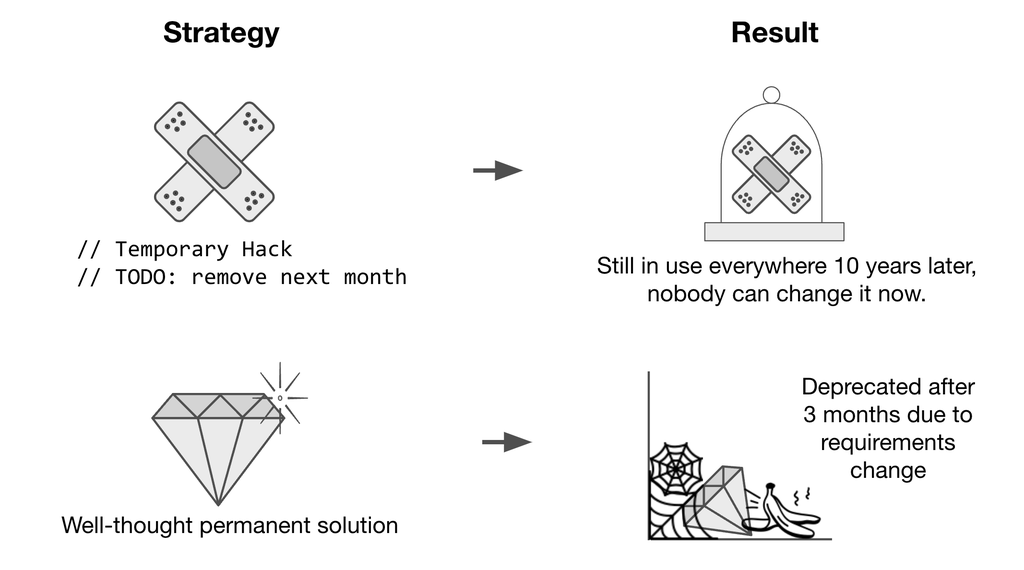

When requirements are constantly changing, and what could come through the door tomorrow is unpredictable, quality takes a hit.

We’ve all looked at bits of code in a codebase and immediately wondered:

“Why on earth is this written like this?!”

The kicker? You don’t even have to be new to the codebase to exclaim that, it could be you looking at your own code from a year ago (Try even a month ago) and you would say the exact same thing.

Software is great at retaining the outcomes of decisions, but the minds that made them for all the possible reasons are everchanging.

This causes chaos, things like production incidents because legacy code context was not accounted for. This is made worse when people with intricate knowledge of the system and codebase leave a project, what could be solved in minutes now takes a meeting of 5 engineers trying to figure out which component fits where. No matter how many processes are put in place, this will eventually happen.

Chaos is an integral part of any software system, without it the terms “legacy code” and “production incidents” do not hold any meaning. Just like there is no such thing as tradeoff-free decisions in software, there is no chaos-free software.

Testing, quality assurance, linting, tooling, code reviews, and automation are all ways to minimize chaos in the software we build.

To free software from chaos, one would have to make the creation process of software deterministic and purely rational. Some would say that would only be possible if the human element is removed from the creation process (I don’t want to start an AI vs Human debate here).

At the end of the day, more than the code, Software is the sum of all the rational and irrational decisions, big or small tradeoffs through the process, all the hours of thought, all the debugging sessions, all the bugs and all the production incidents, and yes, all the legacy code, put together.

As long as humans create software, all of the above will be a part of it. And yet, we find ways to keep building on top of these challenges, build amazing products, and fix bugs tirelessly knowing damn well we’ll never fully get rid of them, refactor code to the point where the original system is just a small part of a much larger system.

May we keep building imperfect software that keeps itself open to evolution.