Let’s build our own CI Provider

CI Pipelines form the backbone of all the world’s best apps. They take away the most tedious, mundane and repetitive part of a developer’s day, writing and executing scripts for tasks that have nothing to do with actually building things.

Without CI Pipeline, every developer would be stuck with the added mundane task of running scripts and processes each time they have to ship or push code to a platform, lengthening release cycles and reducing confidence each time code for an app has to be launched to people.

With CI pipelines being so ubiquitous and easily accessible, with platforms like GitHub Actions, GitLab CI and of course, managed services like CircleCI. I thought, what if I wanted to build something like that myself? How would I do it?

This blog post is a walkthrough of the process and steps involved in how I built a CI/CD Pipeline runner, and what it would take to build it to a fully functional feature-complete solution like GitLab CI.

We would cover the following bits:

- What we want to support

- The schema for our CI files: YAML, JSON or something else?

- Where do we want to run our pipelines?

- Runner Tiers

- How do we access user repositories and clone them on our runners?

- Running conditional step evaluations and executing user-defined commands.

- Storing logs and step outputs

- Managing Timeouts

Some added bits we will cover in not so much detail that deal with the evolution of the product:

- What would the architecture look like if we were to bring in support for teams?

- What would the architecture look like if we wanted to support more than one Git Provider?

- What would we do if we also want to provide ephemeral storage and caching of artifacts from pipelines?

BTW, I’m naming the service ‘SimpleCI’ and still actively adding changes to it, you can check out the repository here.

What do we want to support

We could support a plethora of features CI Pipelines do, but let’s limit our feature set to a few things which we can focus on well. There’s never a limit to what you can build, but it’s important to understand when to stop.

We’ll be supporting the following features:

- Standard file-based definition of a pipeline with support for conditional running of steps for a pipeline.

- Logging in via a user’s GitHub account.

- Selecting the repository the user wants to run pipelines on, and selecting the events on which the user wants to trigger a pipeline on.

- Registration of webhooks on the repository from our backend based on the user’s choice.

- Spinning up a runner (Varying size of runners depending on the user’s choice) and running a CI Pipeline on invocation of the registered webhooks.

- Seeing a list of the latest CI runs, their statuses and logs (Stretch: With filtering between dates and events).

- Environment variables and context data for runs.

The schema for our CI files: YAML, JSON or something else?

Most CI pipelines (In fact all the great ones) support YAML for their pipeline files. We’re going to do something different, for simplicity, we’ll use JSON to define our pipeline steps.

The pipeline will be stored in the .simpleci/pipeline.json file at the root of the repository with the following format:

{

"steps": [

{

"name": "Install dependencies",

"condition": "context.event == 'push'",

"run": ["echo \"Starting installation\"", "npm install"]

},

{

"name": "Run build",

"condition": "context.event == 'push' && env.ENABLE_TESTS == 'true'",

"run": "npm run test"

}

]

}

For now, we’re also going to support only one pipeline file for simplicity, consumers can define steps to run based on the context.event field which we will populate for them later in this post.

You can check out the full JSON Schema specification for the steps here.

Where do we want to run our pipelines?

Let’s look at the concrete requirements for a CI Pipeline Runner:

- Most CI Pipelines have a policy of isolated “workers”, we want to offer something similar, given customers want to run integrations on their code, that code could be strictly confidential and exposing them on shared instances could well be a breach of SLAs.

- Failures inside the pipeline code or steps should not crash the infra that is running it.

- There’s a security aspect where the pipeline should only have access to the current environment and nothing else, otherwise, there can be malicious code that a consumer could run on our servers and potentially poison instances.

- Unpredictable traffic demanding reasonable (but not super quick startup times) for the pipeline, doesn’t have to be instant.

For the requirements above, we will be better off using a pay-as-you-go/pay-for-what-you-use or a serverless platform that can handle spikes instead of having an infra provisioned all the time.

We thus have the following options:

- Spin up an EC2 instance for each run and keep them completely isolated (Unreasonably slow startup, network IO and teardown but full isolation).

- Use a platform like Cloudflare Workers / AWS Lambda / Google Cloud Functions and disable process sharing and create separate tiers of instances for resource usage.

- Use shared workers but use Containers or a VMM like Firecracker to enable process-level isolation.

The How:

- If we go the Cloud Functions / Lambda / Worker route, we can simply make an API call with the runner information and the platform hosting the function will take care of the provisioning of resources. We can even provision them to be started on the creation of database documents in DynamoDB, Firestore etc and replace the need for manual API calls, with a secure internal Pub/Sub channel.

- If we go the EC2 instance/VM route, we need a server to start an instance, clone the runner source code and then execute the steps. For the initial data, we can use the equivalent of AWS’s

User Datathat is executed every time an instance starts up.

Let’s just go ahead with the Google Cloud Functions route for now for simplicity. It provides a temporary file system to work with and supports native provisioning of resources based on requirements such as memory, compute and size.

Runner Tiers

Not all customers are the same and hence their requirements vary too. For a repo just starting, their pipelines might finish in less than 15 seconds, for a larger repo, it might well go on to be active for over 7 minutes and consume over 6GB of RAM. Great CI pipeline providers give their customers “tiers” of runners they can use, which we’ll support as well.

For a start, let’s have 3 tiers of runners our consumers can use and be billed on:

- Standard Tier that gives them a Linux environment, 2 GB of RAM and a timeout of 150 seconds to clone their repository, run their steps and complete the pipeline.

- Medium Tier: Gives them a Linux environment, more RAM, a higher timeout and so on.

- Large Tier: You get the picture.

The choice would be something the user makes in their project settings, and depending on their choice, an API call to spin up the correct runner is made.

In our code, provisioning these 3 would be very simple:

const runnerSettings = {

standard: {

timeoutSeconds: 150,

memory: "1GB",

},

medium: {

timeoutSeconds: 300,

memory: "4GB",

},

large: {

timeoutSeconds: 540,

memory: "8GB",

},

};

exports.pipelineRunnerStandard = require('firebase-functions')

.runWith(runnerSettings.standard)

...

exports.pipelineRunnerMedium = require('firebase-functions')

.runWith(runnerSettings.medium)

...

exports.pipelineRunnerLarge = require('firebase-functions')

.runWith(runnerSettings.large)

...

Registration of webhooks and accessing user repositories

Building GitHub-based sign-in flows is nothing new, we can simply use Firebase Authentication with a GitHub OAuth App with the repo scope to get and store a token that has access to the User’s repositories.

The received token can then be used with the GitHub API to register webhooks (If you want to learn what Webhooks are and how they tie in, check this out) on the end user’s repository and get notified on the events the user wants to run their CI Pipelines on (Like push, pull_request etc - Which will be appropriately added to the context of the pipeline being run as we’ll see later).

The webhook would be set to a Cloud Function which in turn validates the payload received from GitHub for the event, constructs initialData for the runner and spins the correct runner tier instance up.

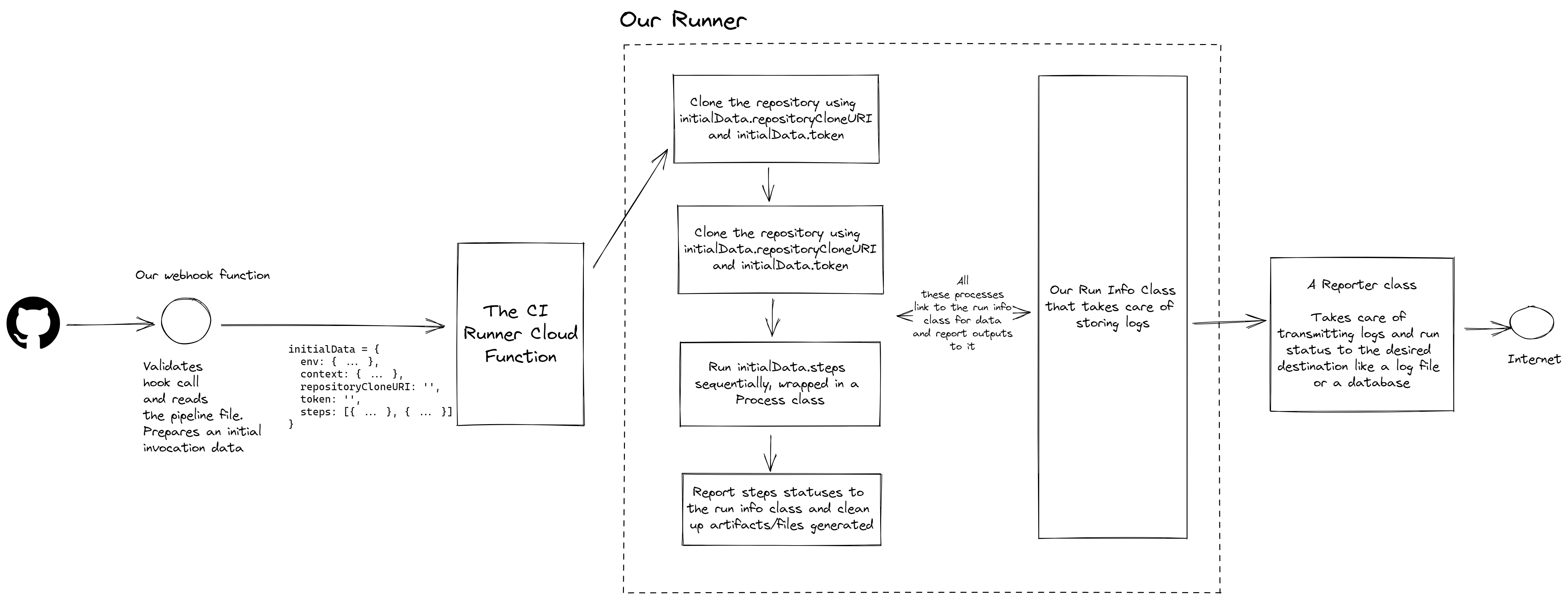

A precursor: Architecture of our Runner and processes running inside it

Every command we run on the pipeline:

- Has to be tracked

- Should not crash our server or exit our process

- Logs from it have to be streamed in real-time and stored on a database.

At the same time, our runner needs access to some data to start a job, the steps to run the pipeline. We do so via an initialData object that’s prepared by our Webhook function, which creates this object with all the relevant information.

Of course, there are several holes in this implementation a seasoned security engineer could find. But that’s okay, once again, an important point to remember is when to stop and say “This is good enough for now”.

Expression Evaluation

Notice that in the steps array, each step has a condition property that evaluates to a JavaScript expression (That can access environment and context variables via expressions such as env.ENABLE_CI == 'true' || context.event == 'push'), the result of which defines whether a step runs or not.

This allows for powerful pipeline files that can handle a plethora of triggers.

A way to evaluate these condition expressions would be to simply run eval and get the value. Although that’s pretty much the only way to do it, it makes sense for security purposes to run it in a separate worker thread that doesn’t interfere with the rest of the flow.

const {

Worker,

isMainThread,

workerData,

parentPort,

} = require("node:worker_threads");

if (isMainThread) {

const evaluateExpression = (expression = "") =>

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

const expressionToEvaluate = `

const env = ${JSON.stringify(runInfo.env)};

const context = ${JSON.stringify(runInfo.context)};

const process = {}; // Prevent process access.

return (${expression});

`;

const evaluationWorker = new Worker(__filename, {

workerData: { expression: expressionToEvaluate },

});

evaluationWorker.on("message", resolve);

evaluationWorker.on("error", reject);

evaluationWorker.on("exit", (code) => {

if (code !== 0)

reject(new Error(`Condition evaluation for step failed.`));

});

});

module.exports = evaluateExpression;

} else {

const evaluationFunction = new Function(workerData.expression);

const resolvedValue = evaluationFunction();

parentPort?.postMessage({ resolvedValue });

}

The environment variable and context information objects are covered in an upcoming section.

Then use the resolved value to check if the step can be executed:

const shouldRunStep = await evaluateExpression(step.condition)).resolvedValue;

This also allows us to do something interesting, we can allow consumers to use context and env variables via something like handlebars dot notation in their run commands and effectively evaluate and interpolate them.

For example:

...

run: "node scripts/.js"

...

can be evaluated and readied for execution with:

import Handlebars from "handlebars";

const stringTemplateResolver = Handlebars.compile(step.run);

executeCommand(

stringTemplateResolver({

env: runInfo.env,

context: runInfo.context,

})

);

Managing and handling process timeout

Since we operate the entire flow inside a wrapper, we also control timeouts. A clean way to do so would be to:

- Keep a list of processes currently spawned.

- Set a global timeout of n - 1 second, where n is the timeout allocated to the pipeline.

- If there are any processes still executing at time n - 1, kill them and mark them as failed.

- Report all logs and errors to your data store and exit the function.

1 second is usually more than enough to handle all these actions, and most worker platforms will also give you an “escape-hatch” that allows you to run some cleanup code before a Cloud Function / Lambda exits for a few seconds, these actions could even be run there.

process.on("beforeExit", handlePipelineTimeout);

Environment Variables and Context Information

Most consumers would expect some sort of environment variables support for their CI Pipelines (Either via an API or regular bash variables), after all, you can’t hardcode secret variables into your pipeline files.

At the same time, there is some additional information per pipeline that is useful for conditional evaluation and inside commands for each step.

This is fairly simple to do. The setup for creation and storage of environment variables is simple:

- Create a variables collection in your database, and allow the user to enter a key-value pair of data for each variable.

- Encrypt those variables with a secret that only your backend knows (Even a hash based on the Project’s ID and some random parameter would be preferable as it prevents complete leakage of variables if your secret leaks).

- Allow users to only override those values and never re-read them.

To expose environment variables in the pipeline, during the setup process:

- Fetch variables for a project.

- Expose environment variables as an object in the expression evaluation (As seen in the section above)

- Run commands to

exportandunsetthe variables to bash for access in Pipeline Steps.

For context data such as the event that triggered the pipeline, expose the context object in the initialData for the pipeline and process step commands via string search and replace for context.VAR_NAME.

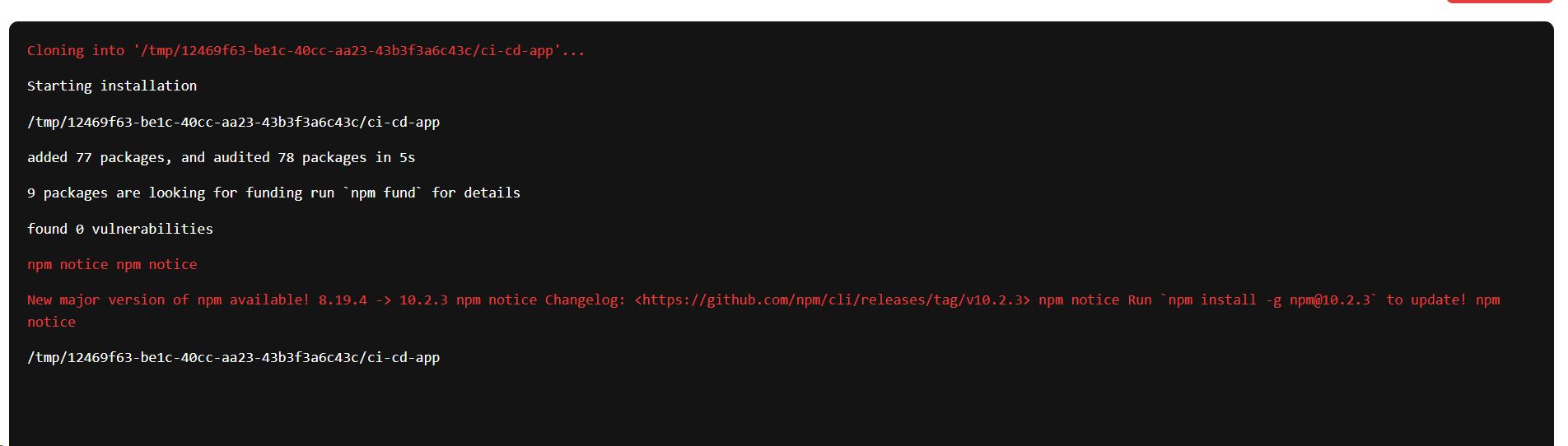

Storing logs and step outputs

Logs are the most important components of a CI pipeline.

For our pipelines, we can create a process wrapper that listens for logs of an underlying process and passes it to a reporter which is responsible for streaming those logs to a log file or a database that supports real-time data pull/push like Firestore.

class SpawnedProcess {

constructor(command, workingDirectory) {

const { spawn } = require("child_process");

this.process = spawn(command, {

shell: true,

cwd: workingDirectory || undefined,

});

this.process.stdout.on("data", this.addToLogs("info"));

this.process.stderr.on("data", this.addToLogs("error"));

this.process.on("close", (code, signal) => {

if (code || signal) {

// Errored Exit

this.finalStatus = "errored";

} else {

// Clean Exit

this.finalStatus = "finished";

}

this.onComplete.forEach((subscriber) => subscriber(this.finalStatus));

});

}

}

We will push the logs to Firestore via a reporter for simplicity and listen to them in real-time from the front end, we can even colour-code them basis our requirements.

Step Outcomes

We’ll do something similar for Step Outputs as we did for Step Logs.

Our steps executor would look like this:

const steps = initialData.steps;

let stepIndex = 1;

for (const step of steps) {

const evaluateExpression = require("../process/evaluate-expression");

if (

!step.condition ||

(step.condition && (await evaluateExpression(step.condition)).resolvedValue)

) {

await markNewStep({

stepName: step.name || `Step Number ${stepIndex + 1}`,

});

try {

if (step.run && Array.isArray(step.run))

for (const runCommand of step.run)

await executeIndividualCommand(runCommand, initialData.runId);

if (typeof step.run === "string")

await executeIndividualCommand(step.run, initialData.runId);

} catch {

// Error thrown in step, terminate execution here and move to unsetting and reporting step

return await markStepEnd("errored");

}

await markStepEnd();

}

}

In our case, the markStepEnd and markNewStep are reporter functions that send/stream the outcomes of the steps in real time to Firestore. This allows us to show an accordion UI for the list of steps in our CI file.

Where the code for executeIndividualStep would be:

const executeIndividualCommand = (command, runId) =>

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

const SpawnedProcess = require("../process/spawn-process");

const clonedRepoWorkingDirectory = `/tmp/${runId}/ci-cd-app`;

const process = new SpawnedProcess(command, clonedRepoWorkingDirectory);

process.on("complete", (status) => {

if (status === "errored") reject();

else resolve();

});

});

Putting it all together

I’m sure this blog post was very information-dense, and that’s how it’s supposed to be. CI Pipelines are marvels of software engineering that keep the best of our softwares running.

For the entire source code, feel free to check SimpleCI on GitHub. I’ve combined Cloud Functions with a Frontend integration flow for GitHub-based auth.

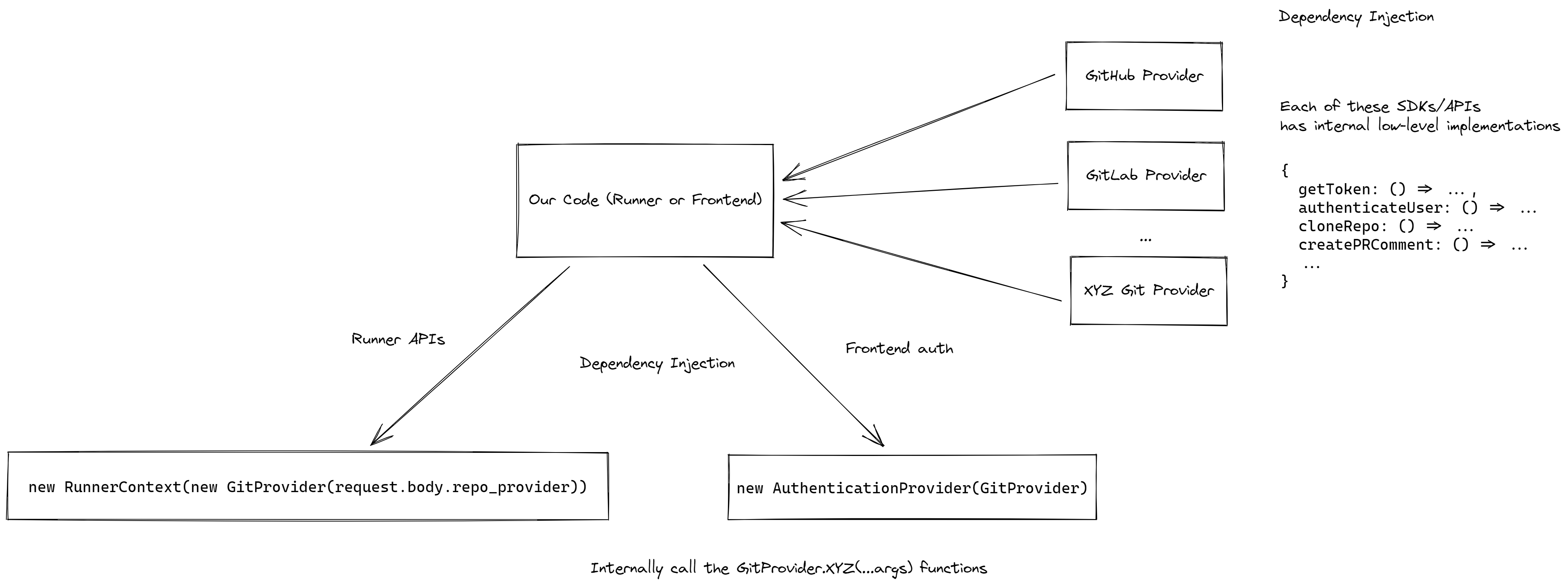

We can obviously add further integrations on the same principle for Git Providers like GitLab, BitBucket etc, which we’ll see in the next section.

Evolution Scenarios

What happens if we want to support a team of users on a project?

This is a very common use case, and this is a solved problem. With each project a user creates they also get a choice to add more users to a project via access control.

We could even create organizations and assign projects derived from repositories to individual organizations to which a group of users have access.

What would the architecture look like if we wanted to support more than one Git Provider?

Currently, in the repo, in a lot of places, the usage of GitHub-specific code is hardcoded, of course, CI Pipelines need to support more than one Git Provider otherwise what’s the point?

In such a case, we need to rely on a combination of dependency inversion and injection patterns. Detailed in brief below:

What would we do if we also want to provide ephemeral storage and caching of artifacts from pipelines?

Most CI pipelines allow you an option to cache or store build/pipeline-generated files somewhere, the implementation details can differ between providers.

Let’s first look at how it will look from our consumer’s perspective. They will only have to add a new object to the steps array with a different field name called type which we’ll have to introduce into our schema definition. The presence of this type field would indicate that the expected functionality is different from the regular evaluate -> run -> print step we execute.

{

"steps": [

...

{

name: "Cache or restore artifacts",

type: "cache-files", // or "store-files". From a pre-defined ENUM

key: "{context.event}-cached-artifacts",

fileNames: [Glob Patterns like './.cache**' or individual string entries],

expiry: Timestamp or a Number indicating the seconds/days they want the artifacts to be available, mandatory file in case of the cache action, we aren't going to store user files forever after all.

downloadPath: // Relevant to when restoring a cache

}

// Repeat this step at the end of the pipeline to update the cache

]

}

Evaluating and parsing the steps array in our runner is fairly straightforward, we just have to add a conditional block to the evaluateAndExecuteCommands function. Let’s take a look at the possible implementation path for artifact storage/caching.

For caching files we can store files on an SSD provided by your cloud to ensure the reads and downloads are faster, subsequently, they are also going to be more expensive than regular

store-filesoperations which we can run simply as upload and download operations to cloud storage buckets.

The underlying process to cache/store would be similar to the following:

- Check the

keyattribute, and make a call to your cloud provider to check if the associated files are available, if not, proceed. - The rest of the pipeline executes regularly.

- At the end, check the cache files step again, and upload any matching generated files from the pipeline to your Cloud Storage Buckets or SSD in case of against the

keyfor further pipelines to use. Also, set TTL to these files in case anexpiryis set.

Make sure to also run these commands in a SpawnedProcess class (Seen above in this post) to have full instrumentation of logs generated by this step for observability from your end user’s perspective.

There was a lot of information in this post, and rightly so given the depth of the problem we’re solving.

I’m pretty sure I’ve missed out on several details but I would be very happy to hear from you what you thought of this. What could be done better and what can be changed completely?

Hope you liked it. Thanks for reading.