Less Work. More Impact.

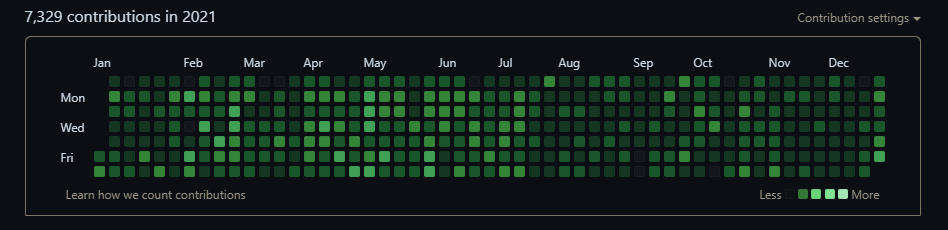

“Your Github profile is a gateway for the world to see how interested you are in your craft” was a piece of advice I read somewhere on the internet while I was in school and hadn’t yet gotten a taste of having a job at a tech company.

That piece of advice is something that I kept with me for a long time, and I vowed to keep my GitHub profile as full of the “green” contribution dots as possible.

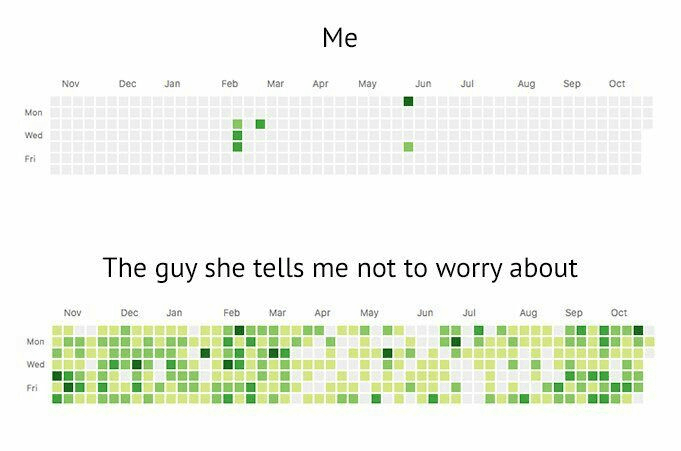

After all, we’ve all seen memes like the following:

This created a sense of “More contributions -> Better GitHub profile -> The better I look to the rest of the world”.

And to an extent, that’s true when Hiring Engineering Managers have to choose between entry-level candidates who’ve all performed well in the interview rounds, your GitHub profile (or any other profile that shows something objective or quantifiable), the projects you’ve worked on while not on the job often turn out to be a tie-breaker as they reflect your drive to get something done and constantly contribute.

The problem arises when people associate the “Number of contributions” on GitHub as a signal of a better and more productive engineer.

Worse yet, when programmers tend to associate more contributions with higher productivity and being a “better” engineer and do that repeatedly day after day, they often end up with performance anxiety when they work on things that don’t add commits to that chart. Even on vacations, there’s always an itch for these engineers to push at least one commit and get that “green box” filled for the day on the contribution chart.

Everything at that point boils down to “Oh I’ve not written code that would show up on my profile, I’m missing out.” or “Days where I didn’t code were not productive at all! Something was wrong with me that day!”.

In this post, we’ll look at why contributions and the number of lines of code shipped is a faulty metric to measure the productivity of engineers and how “impact” is what we should be measuring instead.

Impact

The word “Impact” gets thrown around a lot in the field of Engineering. From the candidate in the interview round, “I drove revenue impact with my changes” as if the entire company was dependent on it to the org leaders using it as a buzzword to get the crowds of people hearing them all excited. What is Impact in the context of engineering?

To me, engineering impact is achieved when what someone does creates value in the form of one or more of the following:

- It increases the productivity of developers working on a codebase.

- It makes systems more robust.

- It charts paths or makes changes in the codebase for the product to be improved.

All of which result in an effect on a company’s revenue or at least goodwill or image.

A developer writing 1000s of lines of “Hello world” code is creating no impact as there’s absolutely no value created, it’s not increasing anyone’s productivity nor is it increasing the revenue of the individual or the company (Unless writing “Hello World” is what you’re getting paid for, in which case, where do I sign up?).

The catch with impact? It’s not easily perceivable by the amount of work a developer is doing. And that’s what brings us to the next section.

Why contributions are a faulty metric: The facade of more commits

Let’s see the types of actions that come under a “GitHub contribution”:

- Commits to your or other people’s repositories

- Pull Requests/Issues raised on your or other people’s repositories

- Pull Requests or Issues reviewed and commented on.

Now, the first metric: “Number of commits” is an extremely manipulatable metric. You could add commits line by line in your 100-line file and voila, you have 100 contributions to show the world on your GitHub profile.

More so, different people have different levels of tolerance for when they feel they should commit changes, which also depends on the situation people are in. People might be making “monkey-changes” where they make a single line config change across 100s of files and might only add that up to a single commit, others when working on large libraries might make sure to commit every file separately to make it easier to revert later on.

In the above example, is one developer less productive than the other? You can’t answer without knowing the kind of impact their changes have. That config change although an example of monkey-work, might save a company millions and the large library might end up complicating the code further to cost hours of lost developer productivity in a month.

The different stages of a tech worker

When you’re fresh into the tech industry, the number of lines of code you write is very important. The focus is on raw output, things like the number of features shipped and the number of pull requests opened and reviewed.

As someone who’s been in those shoes myself, I was always concerned by how many people didn’t code often but were paid significantly more than any of us “junior” engineers. In our minds, they were simply attending meetings all day and coming up with “architectural patterns and designs” once a month or a quarter or performing research work which often felt extremely slow to us.

Granted, several companies make the mistake of over-hiring people, to the extent where they just attend meetings all day, have no knowledge of how the systems are working and simply “drive” what they see and it won’t make a difference if the company had them or not. But that’s not true for all senior hires, they wouldn’t be senior after all if they weren’t skilled, they might just be at the wrong place.

It’s only now that I realize that when you’re new, what you “can finish” means a lot. When you’re a senior, what means a lot is what you “know”. When you’re at the top level, it’s what you can “champion and drive”.

Raw Output vs Creative Work

Throughout your tech career, you’ll have two types of work: Work that involves Creative Output and work that involves Raw Output.

When you talk about creative output, like coming up with solutions to interesting problems no one at the company or even the world has found a respectable solution to, you can’t measure the rate of output. The output or rather the lack thereof does not indicate the person is slacking off, it could take a day or it could take a month but the overall output would be the final solution, partial solutions are stepping stones or “scoped work” where a large and challenging complex question is broken down into smaller parts to make it easier to solve for it. But still, in most cases, the partial solutions will only make sense if they can all be added up and combined into a comprehensive solution that solves the overall problem.

Think of creative output-related work as charting a path in a forest you’ve never been to.

You’ll have to find the way yourself and you might end up in blocks that are unknown and see things you have never seen before. You can neither put targets that by the end of week 1, you would have covered 75% of the forest, which for some reason, a lot of “sprint planning” tends to focus on.

On the other hand, there is raw output. Raw output often follows creative output, and is measurable, sometimes in lines of code, or sometimes in the number of features migrated over from an existing codebase.

As you progress in your tech career, more and more of your work shifts to creative work and less raw output. It becomes more about what you know and what you drive rather than what you can get done.

Less visible “work” and yet, more impact.

Ask the Principal Engineers at large tech companies how important their inputs have been to get the company where it’s at and you’ll know what I am talking about.

All that being said, code is still paramount

If I were to go to an engineer’s GitHub or GitLab profile and I see 0 commits this year, not that big of a deal, but if I see that consistently for the past 4-5 years on their profile, then that’s a really big red flag.

As engineers, the amount of code you write might not be that important at a later stage in your career but writing 0 code is a sign you’re probably not tinkering around and learning as much as you should, given a lot of learning in the field of software engineering is directly tied to practising it via code or building things and systems that we still haven’t found ways to automate.

There are obviously exceptions to this, I know exceptional engineers who have not written any code recently, but that’s an entirely different story. More like an exception rather than the rule.

It’s a lot like writing books, great writers on top of reading a ton, don’t just write sparsely once a year, they keep writing every now and then as that’s a core habit they have developed.

Even famous writers that enjoy all the press in the world, find time to sit and write their minds simply because there’s an itch for their craft that can only be satisfied by writing.

As software engineers, there’s always going to be that itch to write code. By the time an engineer gets to a position where writing a lot of code isn’t required, they would have already written so much code it would have become a habit that either needs to be broken or kept on.

You can’t judge someone’s impact with their number of commits, and no developer should associate their worth or productivity with how much code they shipped.

Different engineering roles have different requirements and the crux of all engineering should be to solve problems, not to write code. This is something experienced engineers understand well but junior engineers don’t.