Inevitable Evolution: Splitting Your Frontend

All apps start from a single codebase, this is even more true for a frontend web application. When an application starts out, all you are looking for is to build an app with a framework or library of your choice. If you were someone starting out before 2021, most likely you would have just scaffolded a single-page application with something like Create React App (Long live) and just went on with your day.

Fast forward a few months, everything is going well, and customers are happy with your app, but the newly hired SEO team comes to you and says “Hey, we noticed our pages don’t rank that well on Google, we need to optimize for SEO for inbound marketing”.

Okay, very valid request from a business perspective. How do we do that? We would have to either change the framework to an SSR-enabled framework or find a way to server-render a part of the website. Both of which are headache tasks that would take some time. This is part 1 of the realization that at the very beginning, you need to be very careful about which framework and libraries you choose.

Sooner or later, you inevitably realize that different parts of the application are interfering with each other.

Problems start to arise over time with a single frontend codebase:

- The home page is a marketing page, why does it include Javascript that is required to bootstrap the dashboard?

- The SEO rankings of some pages need more attention and just can’t work with the SEO framework/pattern we have in place for the web app we started with.

- There is a need for a public blog that needs to be served via WordPress because the recently hired Marketing and Sales team is comfortable only with that framework.

- The team size has increased multi-fold, people want independent deployments and rollbacks for different parts of the application.

Now, do understand that these are extremely nice problems to have. So if you have these problems, good job. These problems aren’t caused by technical debt but rather serve as a sign that the system has outgrown itself and needs some more work to fit into the new requirements.

What do we do about it?

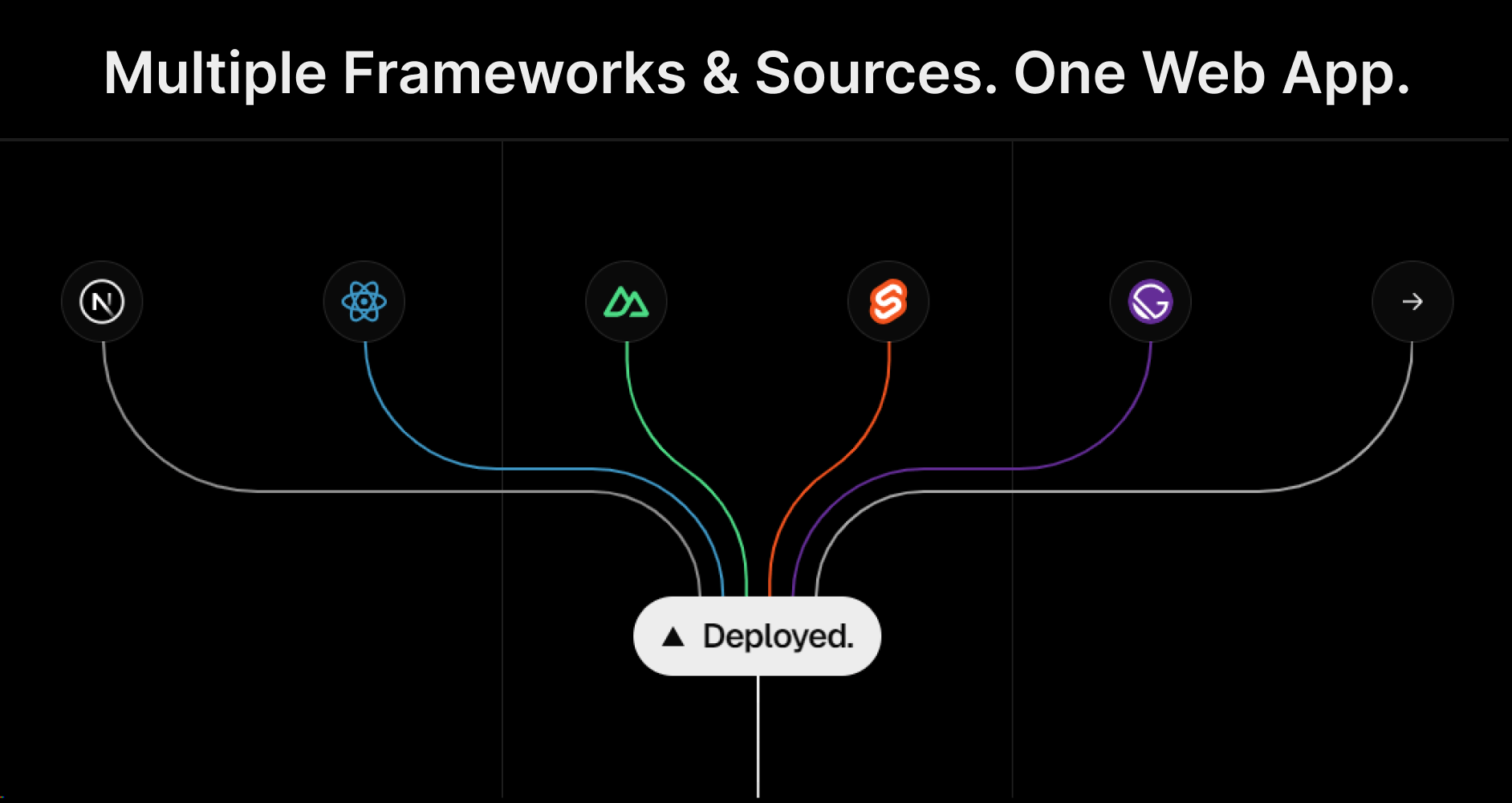

There exist various solutions to the aforementioned problems. The most common solution is to find a way to split your frontend into multiple parts that can be independently maintained, worked on and deployed.

It doesn’t matter how you structure it, it could be a monorepo, or it could be a poly-repo. The end result is that there is a new frontend that is served on the same domain as the old one and the users think they are browsing parts of the same application.

Some common ways to do it are:

- Micro-frontends: These make sense for an application that needs to render different parts of the frontend built separately on the same page. Think of one container application that imports other apps as libraries (Of course it’s a little more tricky than that) and uses them as components of itself. Micro-frontends are amazing but they’re out of scope for this post, stay tuned for an explainer on them soon.

- App-splitting: A simpler approach for public pages would be to build separate projects for public routes and a separate project for internal/dashboard pages and to serve them on separate URLs, either subdomains or same-domain sub-path request rewriting.

We’ll focus on route-based app splitting in this post.

How do we route users?

Now that we’ve decided to split our front end into marketing/public pages and dashboard/authenticated pages, let’s look at how we’ll route users.

The simplest way is to obviously have two different URLs for the apps. Examples of these would be google.com, mail.google.com, photos.google.com. Notice how the apps are split based on sub-domains, so Google Photos and GMail don’t have to share any common code but with the help of cookie-sharing across subdomains can retain the same authentication info of the user. This is how Google Search, Gmail and any other Google service can recognize that it’s you trying to access the site, without having to be one single application.

Similarly, even this site, devesh.tech and blog.devesh.tech uses this approach. The public site is a Gatsby-generated static site while the blog is a Next.js-based Static Site.

That being said, this is very simple to implement (Often a single config change at the Domain registrar level) and poses very few challenges apart from data and credential sharing, which is natively handled by the browser anyway.

The tricky part would be to serve different apps on the same domain, say google.com and google.com/photos with both coming from different source codes.

Let’s look at how we’ll route users.

- Redirects: Quite possibly the most basic way of routing users to a new application. We’ve all seen instances of a site redirecting its users to a new version like v2.site.com. There are problems with this approach though.

- It’s not the most user-friendly way to do it, users don’t like redirects, and all the memory that comes with experiences built over time is lost the moment a new URL and domain are in the picture and you have to do all sorts of migrations to make sure a user can use both versions of the site.

- If you’re working in a larger org, doing this is also very hard to convince the leadership to do. It also sets an expectation in the org that parts of the site operate in different silos, which can lead to a culture of teams not collaborating. It isn’t a big problem for most companies but a problem nonetheless to be aware of.

- Rewrites: This is the approach I personally prefer to use for zero downtime and zero-inconvenience app-splitting. Think of rewrites as showing the browser a URL and serving content from a different URL. With rewrites, you could serve https://example.com from one project, https://example.com/blog from a different project and https://example.com/dashboard from a different project.

There are obviously additional configurations you have to add to both the sites, otherwise, anyone could run phishing attacks on any URL (Imagine being able to serve Instagram.com or facebook.com from a different domain and the credential leaks that would cause).

There are also some nuanced considerations you would have to make at an application level when requests are rewritten, we will see them in the upcoming section.

Real-World: What we did at Solar Ladder

If you go to solarladder.com, solarladder.com/design and solarladder.com/login, you will notice something interesting, the homepage’s design and speed do not match that of the Login page.

This is simply because we serve solarladder.com and solarladder.com/design from a different source than the internal post-login pages at solarladder.com. This is done via a combination of the Same-domain request Rewrites that Vercel (Our frontend host) provides us with.

On the front end, we set rewrites in our vercel.json file:

{

"rewrites": [

{

"source": "/design",

"destination": "https://solarladder-public-....com/design"

}

]

}

Since Vercel is the provider via which our Public Paths repo is also deployed, the rewrites work as expected without any additional headers and rewrite-accepting configurations from the Public Path repo.

Technical: Nuances with Asset Paths

When you rewrite a request of one path to a different page, everything stays the same and the server simply fetches the HTML of the page the rewrite points and sends it back to the browser.

With this, there comes a complication:

Scripts and Assets do not work as they point to /script-${uuid}.js but those files are not available at solarladder.com/script-${uuid}.js and instead are at solarladder-public-.../script-${uuid}.js.

To fix this, Next.js and all frontend frameworks allow us to add an assetPath prefix so when the app is built and pushed to a live environment, it picks up solarladder-public-....com as its base path for generated assets regardless of the domain it is being rewritten to.

This fixes the problem for even Next.js optimized server images using the next/image tag.

Make sure to do the same for static images and assets (Ones stored in the public or static folder, depending on your framework) you point in your public app.

Technical: The nuances with the Homepage route rewrite

This is something you’ll encounter with all SPA Frameworks simply because of how they receive requests and route all of them to the same

index.htmlfile.

Making the redirects and rewrites work on Vercel for the root (/) path was a nightmare, it took me 2 hours post-midnight to figure out and reverse engineer what was going on at a Vercel and the Vite framework level (We use Vite for our traditional frontend, something we switched to a couple of years ago after being in prod with CRA for 3 years).

No matter what I did, the rewrite rule:

{

"source": "/",

"destination": "https://solarladder-public-....com/home"

}

did not work. It simply opened the regular frontend homepage.

To understand why it didn’t work, we need to understand how Vite and other SPA framework’s route resolution works in general on hosts like Vercel:

To fix this issue:

- Post a build on CI/CD, rename the

index.htmlfile tobuild.htmlor some other file name. - Instruct Vercel:

- To rewrite / to the new landing page website

- And to rewrite all the remaining requests to

/build.htmlin a typical SPA fashion.

{ "source": "/", "destination": "https://solarladder-public-....com/home" },

{ "source": "/:path*", "destination": "/build.html" }

Making a 0-downtime and side-effect migration happen

For logged-in users, we want a redirect to /dashboard. In the existing site, it was simple to do on the client side as the Homepage component was configured to redirect the user to /dashboard via React Router if the user was logged in.

To do so now required us to:

- Push a change 1 week before launch to our front end that added logic to create and delete a cookie for authorized and unauthorized users respectively.

- Right at launch, instruct our front end via a vercel.json rule to do a server-side redirect to

solarladder.com/dashboardif the above cookie is present. See Vercel’s Redirects for reference. - What if the user came to the site weeks later but was logged in? In this case, the user would still have an authorization session open via a legacy IndexedDB and localStorage flag we also set since the beginning of the site, since the code is running on the same domain due to a rewrite, the new landing page will have all the access to that data, we read it and we simply do a redirect to

/dashboardon the client side, post which the cookie would be set for them and all subsequent visits to the site would be handled on the server-side itself.

The rule looks like this:

{

...

"redirects": [

{

"source": "/",

"has": [

{

"type": "cookie",

"key": "<authorization-identifier-cookie-name>"

}

],

"permanent": false,

"destination": "/dashboard"

}

]

}

The Result

The difference between our previous homepage’s performance and our new homepage’s performance was staggering. With better SEO and insanely better design of course.

For context, our previous homepage’s performance was 27 even on a desktop!

Our current frontend dashboard is now only for logged-in users and is just that, a dashboard. It does not have to worry about any marketing and SEO pages to serve and can continue to remain an SPA and in the future, the work is decoupled between teams.