Diving into the Engineering of Push Notifications

Ding 🔔 Your Phone Chimes and your screen lights up.

That’s a notification. You frantically pick up your phone, completely breaking your focus from whatever you were doing and hope it’s that person you’ve been messaging for the past 2 days, but it’s not, it’s a notification from Duolingo threatening you to complete your French lesson or you know what happens next.

If it were any other app, you would have uninstalled it out of frustration (Waiting 12 hours for a reply isn’t easy), but since it’s Duolingo and your life is on the line, you open it and complete that Lesson that’s been pending. Duo is happy.

Notifications are distracting and mostly unproductive, and yet, product managers and entire marketing departments rely on them for feature outreach, engagement and campaigns.

Some brands even leverage notifications for better brand awareness and brand marketing. I’m looking at you, Zomato and Swiggy. 👀 I could argue a big chunk of their business comes via nudges they send out to users through push notifications.

This is also exactly why if there were one feature that I would be happy to lose out on, it would be Notifications.

That being said, it’s a marvel how ubiquitous they are and how reliably they are delivered in the tens of billions every day, and without them, a lot of stuff we take for granted each day, would not get done or would be delayed. That notification about your order that got shipped which got you waiting at your door, that notification that today’s weather is going to be rainy so pick up your umbrella while heading out, that notification that your Uber has arrived with your ride’s PIN in it. These are all examples of areas where notifications add a lot of value to our daily lives.

Financially, it’s also extremely cheap for brands to tap into. An SMS costs a lot of money and has a lot of regulatory requirements, push notifications are practically free to deliver via the infrastructure we will see in this post.

There are even some amazing features on notifications like Live Activity on iOS and stuff like being able to reply to notifications right from your notification shade that genuinely enrich user experiences.

With all this in front of me, I couldn’t wait to dive into how everything works. I was in for a surprise though.

Information on how to get started with Push Notifications is plentiful but each post you get on Google is a marketing post trying to sell you their notification service, no one truly explains the process from start to finish. In one part thanks to Google’s algorithm which has deteriorated to such an extent that useful information is clouded by pages upon pages of marketing material and in another part, if there were information readily available on how to work with notifications and implement them, all the companies selling their notification service would not be able to sell it to you that easily without clouding notifications as a mystery land that only the engineers at their company can fly over.

This post is my compilation of learnings about Push Notifications after diving slightly deeper than Page 1 of the Google Search. Let’s get started.

Note: I’m assuming you’ve searched and tried your hands on Push Notifications implementation instructions before. It is one of those topics where the core concepts are missed in favour of quick implementations.

The bare necessities to show notifications in your app

I’ll also be busting a very age-old myth here. You don’t need any service like Firebase Cloud Messaging and Service Workers to show notifications.

All you need to show notifications from your app is permission from the user. Ever visited one of those annoying News sites and immediately received a browser popup asking for permission to show notifications? Or ever installed an app and the first thing you’re greeted with is a prompt to send you notifications? Yeah, that’s the permission bit I’m talking about here.

Asking for permission to show notifications is very simple if you’re running in a JavaScript environment, simply run the following line of code:

const status = await Notification.requestPermission();

// The value of status can be 'granted' or 'denied' depending on what the user selected

Then you can show a notification with another simple line of code:

new Notification("Hi there");

Check the reference for Notifications API and the wonderful things you can do with it here. Since notifications are just logical entities linked to what the system displays on the screen, they also have CRUD APIs to create, and update their content (LinkedIn or Instagram show you a notification and then keep updating it as more activity comes in).

Notice that you don’t even need a service worker to show a notification. Where a service worker adds value is something we’ll see in the next section.

This pattern is the same for all platforms, no platform requires the use of Firebase Cloud Messaging for showing notifications. Notifications are a native platform feature and as long as you have the user’s permission, you’re good.

This misconception that you need FCM arises from a very simple fact: All tutorials online deal with Push Notifications being “delivered” via FCM with a Service Worker on the front end receiving the notification and displaying it to the user.

Notification Segregation

Well, getting permission to show notifications and displaying them to users was fairly simple. Now comes the tricky part, how do you integrate it with your business logic?

Most notifications can be segregated into 2 buckets:

- Action-driven Notifications (XYZ Liked Your Post)

- Marketing and Feature Push Notifications

More often than not, the person who has to receive a notification is not the person who acted on your platform (For example, the person liking a post is not the one receiving a notification about it). In such cases, just relying purely on front-end notification permission and logic might not be enough. We’ll understand why in the next section.

Let’s understand how to handle the delivery of these types of notifications.

Understanding Notification Delivery

In essence, you need a way for your app to:

- Track active users and the devices they are on

- Have a way to handle the triggering of these notifications from one user to the other and potentially batch these notifications.

- Have a way to not lose notifications in transit or if the user is not online, you need a buffer to store the notification.

Let’s build a basic notification delivery system

A basic setup for a simple app with not many users would be a Peer-To-Peer approach:

In case Frontend 2 is not active, our notification server can “buffer” notifications in memory or on disk, till Frontend 2 comes online.

That is it! This is a condensed way all notifications in the world essentially work.

This might not scale or be very effective for several reasons, some of which are:

- This couples notification delivery with frontend web socket pings, we should have background processing of notifications as they are not always mission-critical and frontend calls might fail.

- This exposes vulnerabilities where the notification web socket server is receiving

- Most importantly, this doesn’t handle for delivery of notifications when the app is not active or open, so this is not useful for the engagement of users or marketing notifications, especially where you want to leverage notifications as a way to bring users back on to your system (Tell me, when was the last time you received a notification ONLY from the app you were using at that time? My guess is several apps try to get you to open them via their notifications).

With some tweaks to fix the above pointers, our setup looks a little like this to offload notification delivery to a server and add support for additional types of notifications:

This, however, doesn’t address the problem where if a device is offline or not connected to your web socket server, it won’t receive notifications. We’ll discuss how to fix that problem in the next section.

This is a successful setup even Slack’s desktop app uses to deliver notifications from one user to the other, with several tweaks to scale it for their load of course.

Even on a huge scale, the core architecture and concepts don’t change. And to help us scale is where things like Service Workers, Notification Protocols and Firebase Cloud Messaging come in.

Understanding Notification Delivery At Scale

Why you need Service/Background Workers

I have written extensively about this topic in How to make your Web Apps work offline.

Service Workers are special scripts in web applications, that allow you to run some processing in the background even when t

When it comes to notifications, remember our WebSocket server? Browsers have the capability of connecting to WebSocket servers for Push Notifications (Messages are sent and received via Protocol Buffers) natively which is exposed via their PushManager class that Service Workers can plug into.

This allows your web apps to be offline or inactive and still receive push notifications.

Do note that if a browser itself is closed completely and no background process is running, notifications won’t work and the browser will only show pending notifications when it reconnects to the WebSocket server.

The WebSocket server is something we’ll take a look at in the next section.

What is Firebase Cloud Messaging and how does it help?

Today if you have 10 users, the delivery of notifications is very seamless, you don’t even need the Browser’s Push Manager class, all you need to do is set up a WebSocket connection in a Service Worker and voila, you’re done.

But what if you have 1000 users, 10000 or a million users, or a billion? For these scales, the scalability of your WebSocket architecture itself is a concern. That’s actually where Firebase Cloud Messaging comes in.

Firebase Cloud Messaging IS the WebSocket server that scales to billions of users delivers billions of push notifications every single day and acts as a database for buffering notifications till the user comes back offline, all for ZERO COST!

Moreover, since Firebase is a Google Product, which also owns Android and the Chromium project, on which browsers like Chrome, Edge etc are built, Firebase Cloud Messaging comes built-in on these platforms.

So your Browser’s Push Manager or your Android Device’s Push Receiver already know how to work with Firebase Cloud Messaging and that’s the magic of the service.

This is also why if you search for “How to implement Push Notifications” or “How do Push Notifications” work? After the plethora of ads for the search results, the top results are always Firebase Cloud Messaging related.

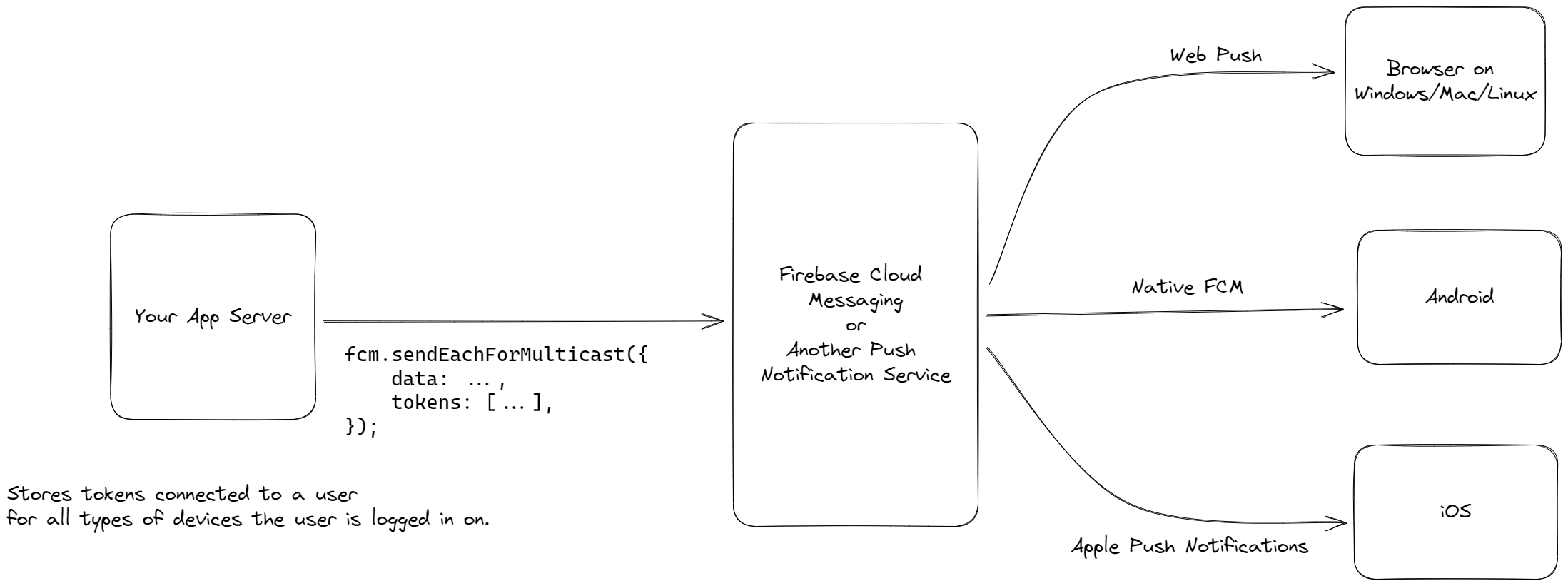

Firebase Cloud Messaging simply abstracts the architecture we discussed in the sections above, the core concepts remain the same. Instead of your own WebSocket Server, you now have API endpoints, Tokens per user/device, and a Project ID (All of which you can get when you create a Firebase Project) using which you can dispatch notifications to your users from your backend.

Notification Tokens and Topics

Remember our basic notification delivery setup from a couple of sections ago? We identified users of the system using their User ID. In the case of an external system like Firebase Cloud Messaging, these User IDs that you generate for your users don’t hold any relevance, all that holds relevance for FCM is the signature of the device that’s connected to FCM’s servers.

Thus, Firebase Cloud Messaging provides you with a token for each device that’s connected, this token contains encoded data of the device, platform etc and takes away the burden of platform-level nuances (Something we’ll look at in the next section).

All you need to do is make an API Call to FCM and it will take care of delivering the notification for you.

// Takes care of getting permission from the user, checking the device, and any specific tasks required.

const token = await firebaseCloudMessaging.getToken();

// Store this token in your DB connected to your internal User IDs for context and retrieval

await storeFCMToken(user.uid, token);

// Now use this token from your server to dispatch notifications

await firebaseAdmin.messaging.sendEachForMulticast({ tokens: await getUserTokens(user.uid), data: ... });

A lot of messaging services including FCM and AWS’s SNS also have the concept of a “topic”, which abstracts away the storage and working of these tokens. You can have multiple users and their devices be subscribed to different “topics” that might be relevant to them (Say for example, Users subscribing for notifications for Instagram posts of their favourite athlete, the topic could be the username of the athlete and any activity from them could be notified to their followers).

The notification delivery system will take care of token retrieval, fan-out and scaling them to be sent to millions or even billions of devices at the same time.

await firebaseCloudMessage.subscribeToTopic('@virat.kohli', token);

Platform Specific Protocols

Push Notifications used to be a feature limited to mobile phones, they are now present on almost all user platforms, including web apps that aren’t even installed natively. Even a website you visited once 2 years ago from

On the web, this protocol is called “Web Push” which is internally built on top of Google/Firebase Cloud Messaging.

On Android, it just connects natively to a Firebase Cloud Messaging server.

On iOS, the protocol is called Apple Push Notifications or APN (Heard that name before?)

All of these platforms have a different way of representing a user device and signature/key, what messaging providers allow you to do is use the same token to represent multiple platforms and not have to worry about any of the underlying implementation details.

For example, Firebase Cloud Messaging gives you a token for any device, but the underlying key could look like this in the case of WebPush:

// This data is abstracted away into a token and stored at the FCM level

const pushSubscription = {

endpoint: '..Some Google Cloud Messaging endpoint...',

keys: {

auth: '.....',

p256dh: '.....'

}

};

// Abstracted by your messaging provider's SDK

webpush.sendNotification(pushSubscription, 'Your Push Payload Text');

Any References to dive deeper into this?

I was eager to learn the underlying mechanisms via which a web browser like Chrome or an Android app connects to FCM Push Notification Servers, listens for notifications and shows it to users.

I highly recommend this GitHub Repository where Node.js processes are enabled to receive notifications via FCM, making push notifications via FCM possible for things like desktop apps built on Electron or using FCM as a messaging system between two Node.js-based microservices (Not recommended but YOLO!).

You can also find this awesome blog post by the creator of the push-receiver package mentioned above where they explain the way Chromium works with Push Notifications underneath and extracting it to make it work for Node.js-based processes.