Creating multi-lingual apps: A starting point

What’s one thing every company wants sooner or later? Well apart from all the obvious, it’s a global audience. Reaching a global audience is never on the charts at the beginning but every company eventually needs to do so for growth. After all, there are only so many people you can reach with an app that only caters to an audience that speaks a particular language or is part of a single culture.

Even if your product is the epitome of convenience for the end user, what if the end user just can’t understand how to use it?

Ever accidentally (or for fun) switched your Phone to a language you didn’t understand and then struggled to find the same language-switching option? Or if you’re using Android, ever booted your phone from recovery mode and had all the instructions in Chinese and just weren’t able to understand what either of the options did? If you said yes to either one of the questions, then you know what it feels like to use an interface in a language you don’t understand.

We build apps for the language and culture we are aware of and expect others to be comfortable with it.

In this post, we’ll be looking at the concept of Locales and the first steps app builders can take to enable their apps for consumption by a truly global audience.

Locales

When one says Locales, it’s not very difficult to understand it has something to do with “place” and “culture”.

A quick Google search for what it is, reveals to us the following:

In software, the definition for the term is extended to reflect language preferences along with smaller preferences like how they write the date, which direction they write their languages (Arabic goes right-to-left as opposed to left-to-right) and even the number system they use. Each device or browser allows its users to select a locale or have a default one depending on the region the user is in.

A single country can have multiple locales and multiple countries could. A user sitting in India could even set their browser/device’s locale to a different country’s locale (I live in India and I have my locale set to the UK for the language, date and number system preferences).

Internationalization vs Localization

There’s one important distinction I want to get by quickly. It’s the difference between internationalization (Often shortened as i18n) and localization (l10n). In most contexts, these terms are used interchangeably, but they couldn’t be more different.

Let’s take an example to understand, let’s say we build a ride-hailing service that starts its operations in the USA, after a while, management decides they wanted to expand their scope to other countries, say India.

Now for an Indian expansion, offices are opened in the capital and the translation is enabled for the app in the most common language in the country (Let’s say Hindi) and allowing for usage in the default language. This is internationalization and can be seen when companies like Booking.com, Airbnb, Uber or a plethora of others expand their offerings to a global level.

Now, a few months pass and the company realizes they want to expand to more cities in India. But they realize there’s a problem, the language changes when you move to a different city and not everyone speaks Hindi, especially the drivers targeting + The culture is different (Like paying by cash is the norm instead of online payment methods, settlement periods for drivers need to be shorter otherwise drivers won’t sign up, people also prefer ride-pooling etc).

So the company introduces these changes to accommodate the needs of the people in the region it is expanding to. This is called localization. The customization can be in the form of adding the region’s language, changes based on culture or just modifying the look and feel or content of the app to suit a region’s needs (Do note that in the above example, we haven’t crossed borders, we’re still in the same country).

In all cases, not accommodating both Internationalization and Localization into your apps can result in detrimental (There’s no point if no one can use what you build) performance and tarnished brand image.

Let’s build a multi-lingual app

With the terms and definitions out of the way, let’s look at how we can leverage frameworks/libraries/services/patterns to build a multi-lingual app.

Simplest Solution: Rely on a Translation Service

Ever used Google Translate? I mean, who hasn’t?

Turns out most browsers will have some form of a translation service integration to automatically prompt the user to translate the page if it detects that the language on the page does not match the one selected by default in your browser.

A simple example is below, most of your users will have this option depending on the language used on your webpage.

This is a good starting point for all apps and most apps would not need more than this, plus there is no engineering effort required here as this functionality is built into most major browsers.

But you can also send strings from your page to the Google Translate API to translate them and inject the translated strings back into the page.

There are a few things one needs to note if one goes ahead with this barebones solution:

- We know how inaccurate translations can get with such tools (Trust me on the number of memes I have seen about incorrect translations from such services). As such, the text needs to be tested in various languages first before being added to the source code.

- You also don’t have any control over the final result of translations that you get on your web pages, the underlying API could change the way they translate specific words or sentences.

- It’s also much more difficult to do the same thing if you’re building a mobile app, something that a translation service will never have direct access to.

Naive Solution: Create multiple versions of your app for multiple languages

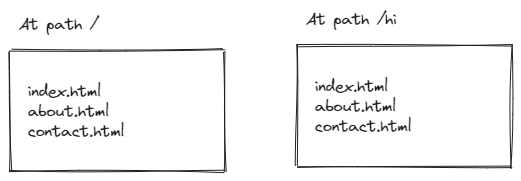

I’m pretty sure the solution I’m going to mention is the first solution that pops up in the mind when someone asks for a simple way to introduce a new language, especially for a website, which is of course, to create multiple versions of your site in different languages and serve them via either a CDN or a separate route like /in. For a long time, this was actually how things worked.

I probably don’t even have to tell you why this is a bad option. For one, it breaks a very important rule: Don’t repeat yourself, the opposite of which is exactly what’s needed for this approach to work. Don’t even get me started on the maintenance effort of syncing content between two completely different versions of a website.

Even for a large company with dedicated teams to manage locale-based content, it can become a mess trying to push org-level changes that reflect on all versions of the app.

This approach does make sense in some cases however, one such case is static blogs where content is written and then HTML or Markdown files are generated for consumption at build and hosting time.

/:blog-post-slug/:blog-post-id

├── index.html

├── hi

│ └── index.html

├── es

│ └── index.html

└── pr

└── index.html

Although even in this case it just makes sense to use a CMS-based solution, something that’s discussed towards the end of this post

Another case where it works is mobile apps that are built and distributed separately for geographical regions. Since apps are stored on the user’s device and consume storage (Larger apps tend to be worse off in terms of downloads and performance), companies prefer shipping versions of the app separately, not just for language reasons but also for cultural reasons.

Do note that there doesn’t exist a limitation on building different apps from the same source code, you can have the same source code and simply build the apps separately for different geographies and use built-time variables to define the language selection for the app.

You can’t build a large website with this approach though, most websites that have routing configuration for different languages do so via a system called Internationalization Routing, where you support multiple languages and use the routes to determine which language you want to display content in. Most of the time, it’s just the same frontend template served to everyone while the backend services responsible for rendering or providing content to the site do so based on the language they infer from the route.

Prerequisite for all of the next pointers

a. Stop using hardcoded text in your source code When starting out with your application, the easiest way to convey information to users is to, well, add it as text in your source code.

But those seemingly small and harmless “Please try again later” or “Sign In to access this feature” texts that are hard-coded into the source code cause a lot of problems and refactoring effort when you are suddenly hit with the requirement of adding support for more languages.

To counter this, stop hardcoding strings into your source code. We’ll look at good ways to work around this in the upcoming sections.

b. Start creating translation files

Okay, so we’ve established that using hardcoded text is not the way to go, where do we keep the text then?

For starters, most applications prefer using translation files, specific to languages and locales:

.

└── translations

├── en.json

├── hi.json

└── es.json

Each translation file could look something like this:

// en.json

{

"SIGN_IN_MESSAGE": "Sign in to your account"

...

}

Depending on the architecture of your app, you could also decide to store these labels in a database, although database round-trips are more expensive as opposed to using translation files that are stored on the server or the client.

You can also store multiple language translation files for the same country to enable localization.

c. Decide on a way to detect the user’s preferred language and give them the option to select a language

Without the ability to detect and set a user’s preferred language, your app wouldn’t really be multilingual.

If you’re on the web, you can detect the user’s selected language using the accept-language header which will contain the locale and language the user has selected on their device/browser. This however takes you only so far, simply because people don’t usually change the language of their devices, or just don’t know where to go in their devices to change the language.

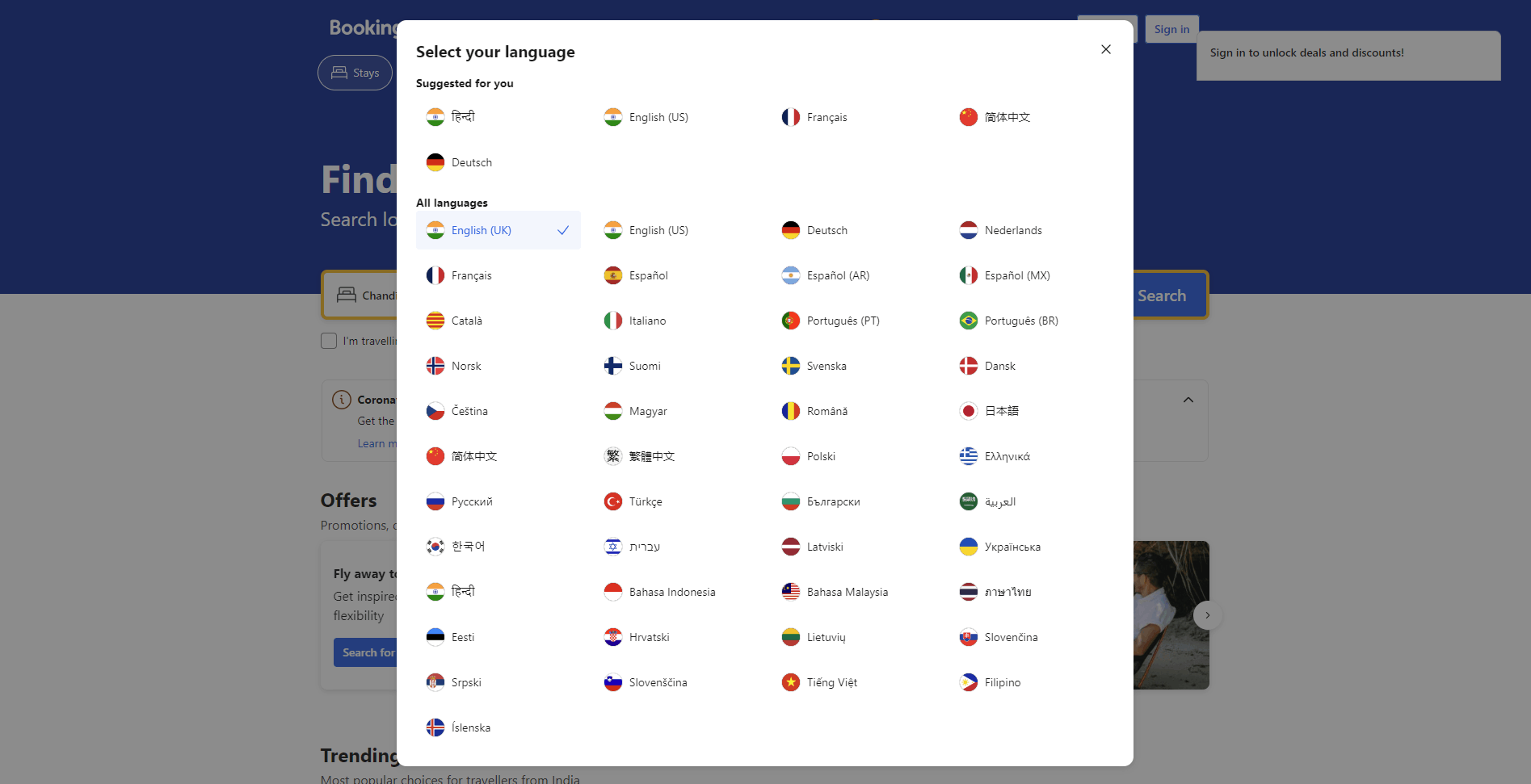

You could provide the users with an option to select a language by showing a prompt at some part of your app (Most commonly it’s the header or the footer of the app)

For example, booking.com provides its users with this modal to select the language they prefer to use for their experience.

Once the user selects a language, you could choose to store it in a cookie or reflect it in the URL, most websites add a suffix to their URL path like /in/hi to reflect a language preference, this URL can then be used to detect the preference on the server and send back the required content.

The flow would look like this:

Option A: If you’re rendering content server side: Templates

This option builds on the diagram above and assumes that you’re rendering your content with the help of a server via an option like a template engine.

<a href="">

</a>

What this allows you to do is parse your markup for variables, and replace them with the appropriate language-matched text.

Option B: Using libraries and frameworks that support multi-lingual app development with Routing

Depending on the framework or library you’re using, you would most likely have access to libraries that take care of translation and routing between languages for you.

For example, if you’re using Next.js, it has internationalisation routing built-in and functions to set and remember a locale. This feature can then be paired with libraries that do i18n translations.

The catch? You have to define the translation for labels, similar to the server-side templates approach.

A simple implementation for a translation library could be of the following form: Use a function that accepts a label and returns the right language-based value for the label from the translation files.

The translate function could look like this:

// The translation files can get pretty big for larger apps

// So make sure to adopt code-splitting and lazy-loading strategies

import en from "en.json";

import es from "es.json";

import hi from "hi.json";

type LangCodes = "en" | "es" | "hi";

const DEFAULT_LANG_CODE = "en";

const languages = { en, es, hi };

const translate = (label: string, langCode: LangCodes = "en") => {

const langJSON = languages[langCode] || {};

if (langJSON[label]) return langJSON[label];

// Match not found, in development mode, throw an error so the programmer is aware of missing translations

if (process.env.NODE_ENV === "development")

throw new Error("Translation not implemented for label: ", label, " in language: ", langCode);

// On production, return the fallback from the default language map and fallback to the label

return languages[DEFAULT_LANG_CODE][label] || label;

};

And you could use it in your code like this:

// React/JSX

<h1>{translate("headings.sign-in-page")}</h1>

// Plain JS

button.textContent = translate("headings.sign-in-page");

One of the cleanest implementations of this pattern can be seen in Excalidraw, they published a blog post on how they achieved multi-language translation and it’s an elegant read.

Option C: Centralized translation service

Storing all translations on the client side might not make sense for large apps, you bloat up the bundle sizes if you’re on the web and bloat up the overall app size if you’re building a Mobile App.

So Engineers have the chance to do what they do best anyway, separation of concerns. I.E: Move your translations to a database, and expose an endpoint on your backend that can receive labels and send back the translation for the label.

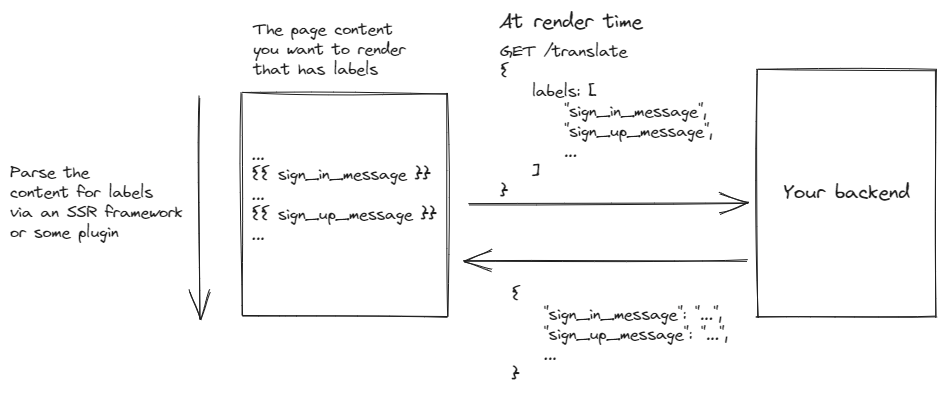

One might ask? Wouldn’t that be too many network round-trips? Well yes, but to combat that, we can send all the labels on the page at once (Via source parsing using a plugin like Webpack or an SSR framework) and get translations for all of them in a single round trip.

Let’s talk about dynamic content, shall we?

One thing that’s often missed is that apps and websites today have dynamic content more than ever. Consider, for example, an ed-tech site that serves videos to its users and shows a description and title below it.

What do you do about the content that’s stored in the database? Like the link to the video, title and description? They’re all not part of the knowns in your codebase and can’t be translated via the options we have seen above.

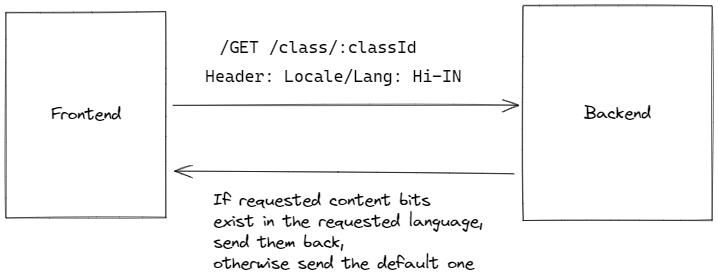

The approach most solutions tend to take in this case is to have a backend that’s capable of storing content in multiple languages associated with the same entity. For instance, the class’s video could be stored in different languages in the storage service, and all the metadata about the class could be stored in different languages as well.

From a product perspective, where creating multiple versions of the same video is not a feasible option, companies usually employ filtering out language-based content or they simply translate only the bits of the content that can be translated like the title and description.

One example of a system that supports this functionality out of the box is Strapi, which allows you to store versions of whatever content you have, in different locales/languages.

This approach does require some additional effort at a data-entry level, and it also requires effort when a product decides to add a new language to its offerings. Still, there’s no way around it unless there is a way to mass-translate content in a database in one go.

Some things to consider

Since we’re reaching the end of this post, it’s important to note that this is not a full list of everything you can do to build multi-lingual apps, each app has its own use case and complications. This post merely acts as a starting point for that journey.

There are some things I would like to point out for you guys to consider:

- Different languages have different writing styles, I.E: Some could be written right to left. If you’re building a web app, it makes sense to automatically change the direction of content based on the inherent nature of the language:

document.documentElement.dir = currentLang.rtl ? "rtl" : "ltr"; - With changing of locales, a lot of factors other than language also change, such as the currencies of the users and the number system used by them (Millions vs Lakhs and Crores) and who can forget? Dates! It might make sense to include such conversions in your scope if your app deals with money.

- Unrelated: An often overlooked aspect of a global app is the tech, when you expand to a new country, the resources you serve to your users also need to reach them fast, and enabling that involves a plethora of tech challenges like replication and content caching at a CDN. After all, there’s no point in being a global app if a global audience can’t get what they’re looking for in time.

The journey from a local app to a global app is a long one, and I am definitely not the best one to consult for all the bits that constitute such a migration. The above-listed patterns are not even all the patterns that exist to build multi-lang apps, and different apps depending on their use case can have different implementations. The multi-language setup is merely one aspect of what can be done and I can’t wait to see what many apps have in store for this journey!