Building our own Serverless Platform

“Now, you just click Publish and AWS Lambda will give you an endpoint to run this code on the cloud and handle all scaling for you” A tutorial I was watching in the middle of the day in my internship several years ago.

We were trying to build a setup where a user would add a new bid to an ongoing auction bidding and that would trigger a “job” that would do some processing and update the timer for our users in real-time. I had thought let’s do it via an API call from the client device, but it was pointed to me that the client device isn’t guaranteed to be reliable and having a server up and running for something like this isn’t wise and we should use something “serverless”. Too bad my lead didn’t explain to me what serverless was and headed into another meeting.

Wouldn’t serverless have meant doing everything on the client device? Which was exactly what we were trying to avoid? Oh boy, could I not have been more wrong.

I quickly realized that serverless was this shiny paradigm where you can write your code, and someone else takes care of managing servers, providing a subdomain for executing your code, managing its SSL Certificates and auto-scaling for you, and that too at a fraction of the cost it would have taken me to write my code and deploy it to a server that was running 24x7.

This convenience was incomprehensible to me. With a single server, I had to pray there was not too much traffic. But with serverless, the platform took care of adding more instances as traffic came in. You only paid for what you used, so if there were jobs that should have run only on a new bid being added to the database, I would only have been charged for that usage + On most days when there was no bidding there was no charge at all. To top it off, there was a generous free tier which I don’t think that product has still burst through to this day.

I quickly realized what the hype about serverless was and why that hype was well justified.

Since the introduction of services like AWS Lambda, Google Cloud Functions and Cloudflare Workers, a lot of businesses have been able to move faster and work on their core business rather than having to worry about provisioning and scaling their infrastructure. And the space is evolving rapidly, with new services and offerings popping up everywhere.

Serverless has also allowed companies to run extensive automation on parts where it was incredibly hard to do so in the past. Things like bank document verifications, auto-translation of articles, auto-tagging of people on photos uploaded to Facebook and much more that we take for granted in our most used apps often build on top of integrations with these serverless offerings. It has also allowed architectures to evolve where services built by engineers can stay decoupled and can be spun up “as and when” needed, saving both cost and time.

A less noticed fact is that there’s also an entire multi-billion-dollar industry built on top of lambdas that makes it easier for users to host their websites and apps online with platforms like Vercel (Which builds exclusively on AWS and uses its serverless offerings for stuff like Edge Functions, Middlewares).

With this technology being so ubiquitous and yet so little understood, I decided to dive slightly deeper into it. In this post, I’ll step into the shoes of the tutorial guy and walk you guys through how we can build our own serverless platform for us.

Do take this with a grain of salt, I’ve explored the principles of serverless and how we could mimic its capabilities with our architecture. But there’s no one silver bullet architecture and I’m limited by my understanding, an engineer with a decade more experience than me in this field will build an architecture far more robust, but this is merely a starting point and documentation of my learning and exploration.

Topics Covered

- Some core principles of serverless computing

- Isolation - Introducing Docker

- The build process

- Writing our functions

- Containerizing our functions

- Hosting function containers

- Let’s get some servers? - Overview of our deployment architecture

- How do we ensure scaling?

- More from here

Some core principles of serverless computing

It goes without saying that serverless does not mean “No servers” (No shockers there). There are still servers, but the one publishing their code on a “serverless” basis has no idea of the underlying infrastructure, nor do they need to care about it. The platform takes care of it.

All serverless computing platforms instruct publishers to write code in an opinionated way. Google Cloud Functions requires publishers to write their code as an Express.js Server controller or a Flask Request if you’re using Python. AWS Lambda asks publishers to write code in a single function and return a value; the value returned is passed down as the response to the consumer.

There also exist some serverless platforms that let you bring your environment to the cloud, we’ll take a look at this in the Docker section of this post.

If you were to make 100 requests in parallel to these platforms, there might be 100 separate instances of your function invoked in parallel, which will scale up or down depending on traffic. These 100 instances are “isolated” from each other, i.e. context from one instance does not leak into the other one and each processes data accordingly (Note that some providers allow for context to be shared in back-to-back invocations but not in two invocations at the same time). This helps prevent crashes from happening and taking the entire server down.

The first start of these functions would often be slow, due to what’s commonly referred to as a “cold-start”, i.e.: Functions need to be fetched from a registry, dependencies resolved and mounted and the server started to respond to a new request. The subsequent requests are often much faster as these function instances are kept idle/warm waiting for the next request for some time.

Isolation - Introducing Docker

As mentioned in the previous section, serverless platforms guarantee the isolation of each function process that is running. So for example, if there are 5 requests to the function at the same time, 5 of them would run separately and have no idea of each other.

This is crucial because you want to ensure resources are not constrained (Locks on resources won’t cause the other processes to wait indefinitely and add latency to responses) and execution is consistent. It also allows for scaling to happen easily as instances of your function could run on several different machines split across the globe, not having to worry about the other invocation.

While this might sound like an easy thing to do, it is fairly hard, because at what point do you say “your process is isolated”, is it at a file-system level? Is it at a memory level? Or is it just a simple “One of my processes crashing will not take the other processes down with it”?

Serverless defines isolation as the most core-level of isolation, where each function instance runs with its own File System, its own memory and CPU and even its own Operating System, often via Hypervisors on top of bare-metal machines to split the machine into several Virtual Machines (Sometimes via tech like Amazon’s Firecracker), each of which run isolated function instances on top.

Thankfully, we have technology at hand to take care of most of that for us (Getting Hypervisors and bare-metal machines and running them would be a nightmare and super expensive). It’s called containerization. Tools like Docker create a “container” for your application that can run in complete isolation, with its own file system, memory, and Operating System (Doesn’t need to be the operating system running on your machine, could even be Linux if you’re using Windows). Best part? Your app crashing inside the docker container does not take down other docker containers running on the machine, other docker containers won’t even know that something else is running.

Needless to say, Docker is too complicated to explain away in this post, you can check more on Docker in this video to get introduced to the concept of a Dockerfile.

Now, what to do if you need to share data between processes? Then serverless isolation is not for you.

There is one trick up your sleeve though, if you want to share data between multiple invocations of your function, you can use the shared memory space of a function instance, but that will only come into the picture on “subsequent” invocations (Your instances are re-used for future invocations) and not “parallel” invocations.

Your serverless platform often keeps function instances idle for some time before terminating them, so that requests in the future do not have to experience cold starts very often.

// Variables defined outside the main function body are retained in memory

// between function invocations on the same VM

let cachedMongoDBConnection;

/* { [userId: string]: any } */

let cacheBetweenMultipleInstances = { };

function getDataForUser() {

if (!cachedMongoDBConnection)

cachedMongoDBConnection = setupMongoDBConnection();

// ... Actual function body

}

We’ll account for this in our setup in the following sections.

A Quick Overview

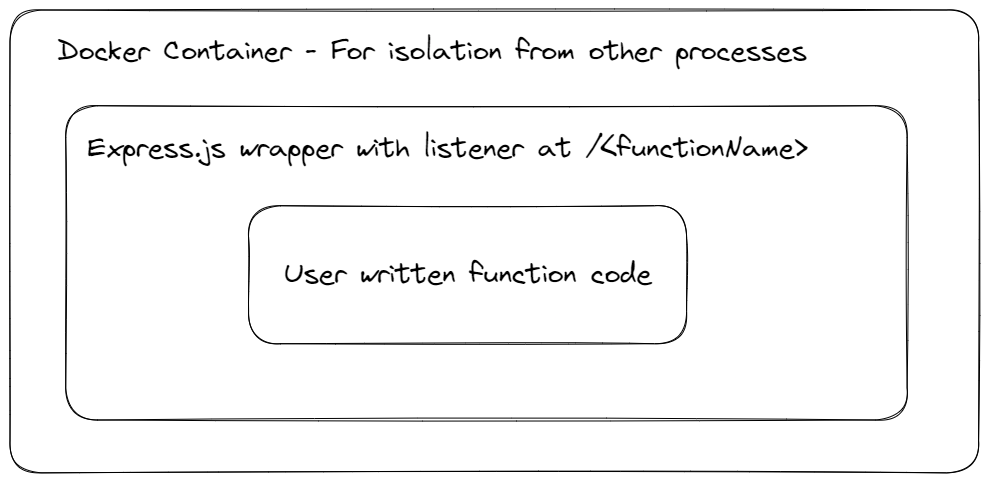

Under the hood, your code is simply “packaged” and wrapped with something that can accept requests, call your function and send back a response.

For example: Firebase/Google Cloud Functions individually wraps your function code as a single Express.js controller.

And that’s what we’ll do too.

The Build Process

Writing our Functions

We’ll do something similar, let’s define a “spec” based on which a user can write their serverless function in JavaScript.

// Heavily inspired by Firebase Cloud Functions

module.exports.myFunction = {

func: async (req, res) => {

// req, res will be populated by our wrapper server

return res.send("Hello");

},

config: {

timeout: 10_000

}

};

Our Express.js server will import this function from the user-defined file and pass the request and response objects for the function to consume and also take care of configurations such as user-defined timeouts, memory limits etc via the config property.

You can check out the code for the wrapper in the GitHub repository.

The published wrapper package is available on npm.

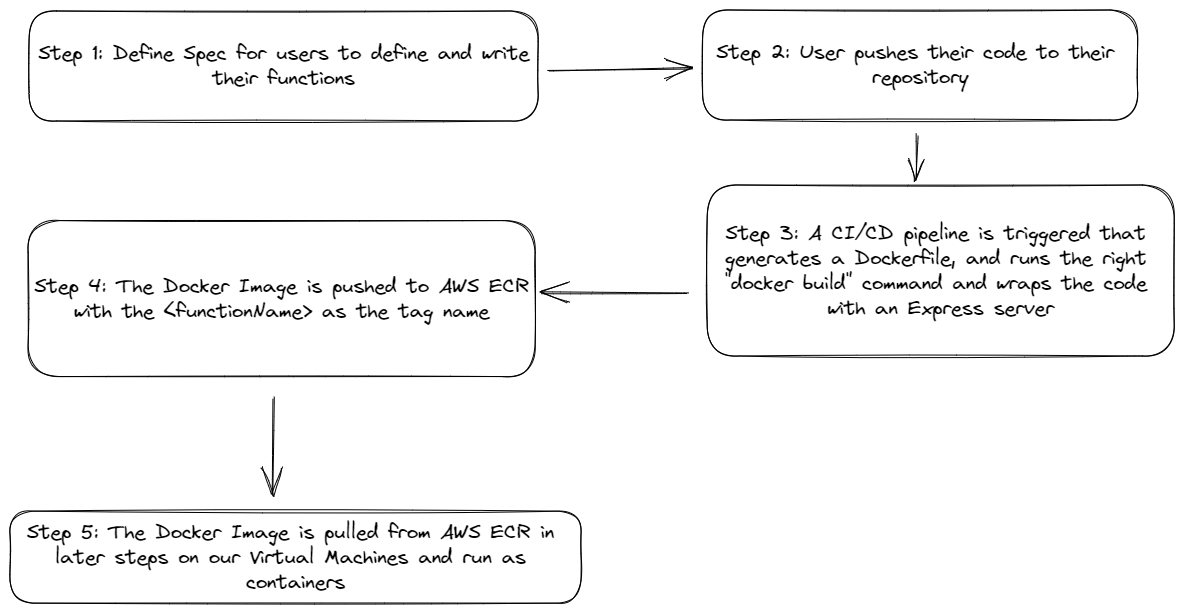

Containerizing our functions and hosting Docker Images

We have the wrapper utility available from the above step, how do we incorporate it into a Docker Image for deploying to our users?

The process is fairly straightforward. For instance, Google Cloud Functions uses Google Cloud Build, where once you run firebase deploy --only functions:<your-function-name> from your Command-Line, the Google Cloud CLI tool picks code from your current working directory, pushes it to Google Cloud, runs a Docker build command and pushes the results to Google Artifact Registry.

We’ll do something similar, but for simplicity, I’ve just created a GitHub Action that generates a dynamic Dockerfile to build and create an image that we then upload and host on AWS Elastic Container Registry for use in later steps – This is from an AWS perspective but for other providers the concept remains the same, we push our containers to whatever platform is available to us like Docker Hub or Google Cloud’s Artifact Registry.

The reference Dockerfile is here and the GitHub Action is here.

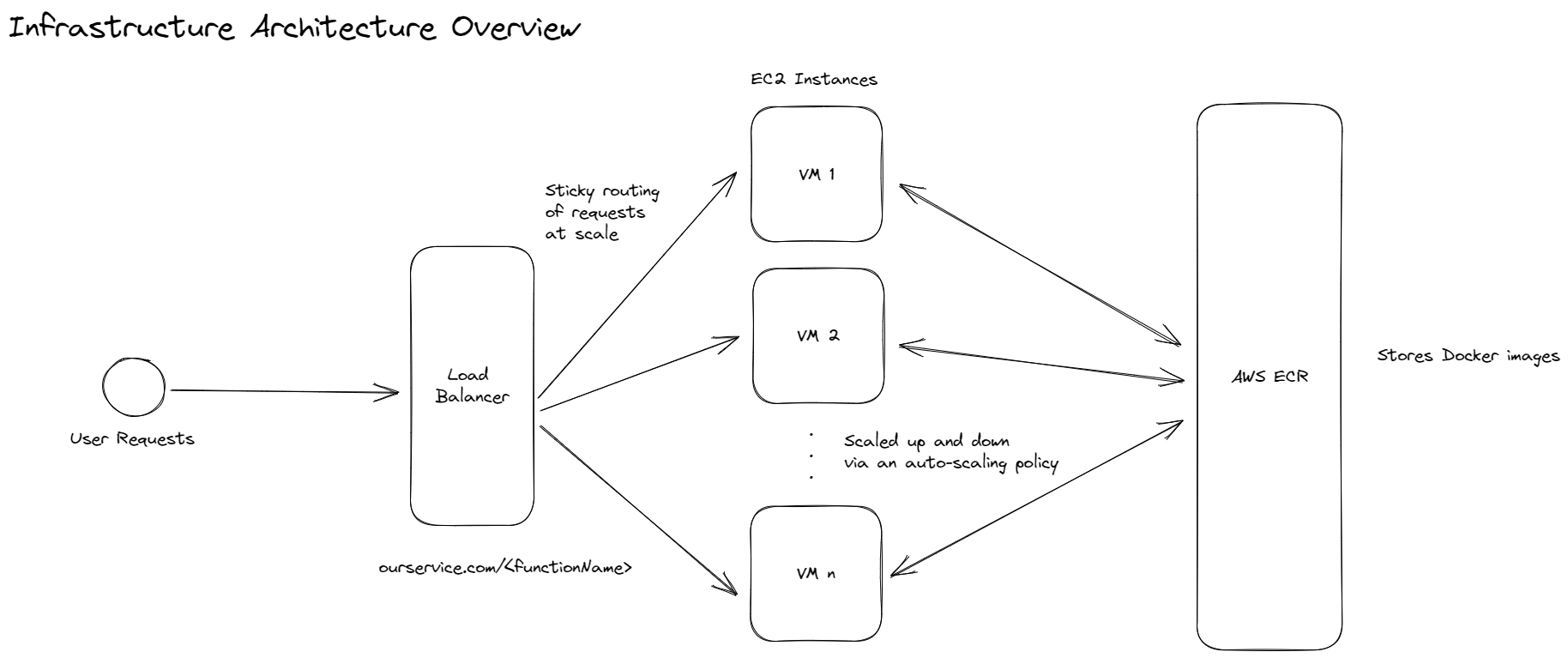

Let’s get some servers? - Overview of our deployment architecture

As mentioned in an earlier section, serverless is just an abstraction and you still need a server to run your function (now Dockerized Containers).

We’ll use a set of EC2-based VMs with Docker installed on them, attached to a load balancer (To queue additional requests and handle routing) and an auto-scaling group linked to number of requests or memory usage per server to ensure a surge in requests is handled by adding more VMs (There are obviously nuances, which we’ll see in the next section).

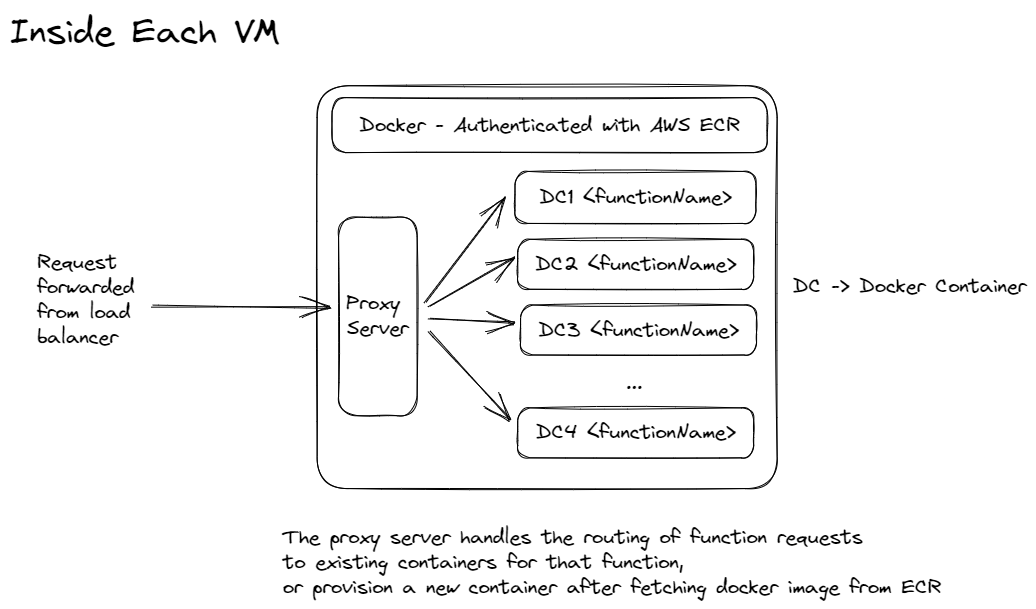

Each EC2 instance will run a gateway server that takes care of pulling Docker images from AWS ECR, and then spinning up Docker Containers for a Cloud Function.

We’ll have sticky routing based on the function name to ensure that requests to a single function stick mostly to VMs that already have their containers already provisioned, this reduces cold start times caused by having to pull docker images from ECR and then starting them up each time a new request comes into a different VM than last time.

You can check the code for the gateway server here.

How do we ensure scaling?

The great part about serverless is that you can rely on them to scale your function as much as needed based on the traffic it receives. Well, there is an asterisk to it.

For example, serverless platforms such as Google Cloud Run have a concurrent maximum instances limit of 100 by default, which can be increased to 1000. This means that even if your function receives a million requests at once, the maximum number of instances that serve the request will only scale up to 1000.

This is fine because not every request has to be served immediately, the load balancers and proxies sitting in front of your functions can wait for your functions to process responses, and queue any waiting requests (The client wouldn’t know this, and simply notice that the latency of requests has increased - This is also why at high loads on even powerful servers, you see degraded performance because the requests are most likely getting queued, and waiting for addressal at the server to prevent choking).

Some providers also limit the maximum number of invocations your functions can get per second. For example, the terms might state you can only get say 3000 requests per second otherwise the rest will be queued or rate-limited (An SLA to queue will not be provided because you would have already crossed the promised 3000 RPS limit).

Another thing to note is that, if you’re running the Hardware yourself, there is no “auto-scaling” because you can’t just create servers out of thin air and add them to your server farm. This is the constraint AWS and other cloud providers running bare metal servers in their data centres have, their hardware is still limited. So they would obviously be employing a bunch of strategies:

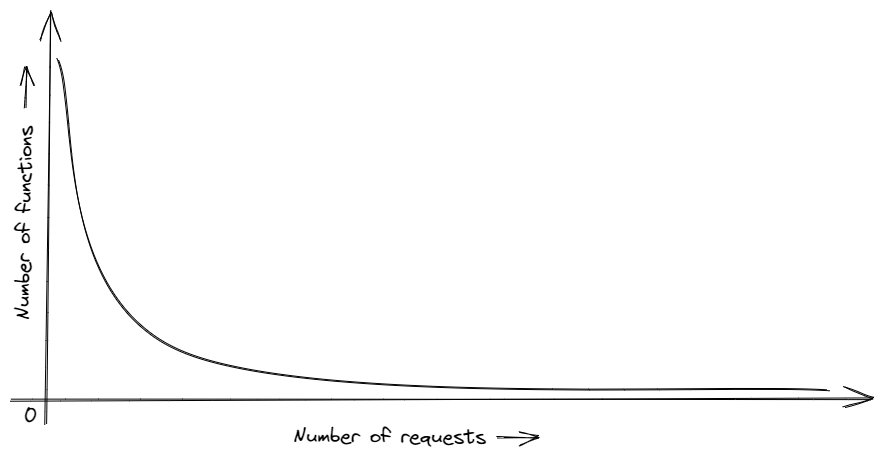

- All functions are not equal, if you were to plot the number of requests to the number of functions, you would see a skewed curve. A very small number of functions would be responsible for a very high number of requests, you can allocate more resources for such functions/organisations to combat this.

-

You can analyse the number of functions deployed and the number of requests the platform is getting, and add bare-metal servers to your clusters over some time if load consistently increases.

-

The data centres often keep spare instances with plans for months or years in advance to combat resource crunches. I’m pretty sure AWS has more bare-metal servers that Lambdas run on than there are actively being used.

-

A combination of automation for all the above, these are very complicated scaling systems and providers have tons of data and analytics to predict load for handling resource provisioning and allocation.

What about our setup with auto-scaling groups?

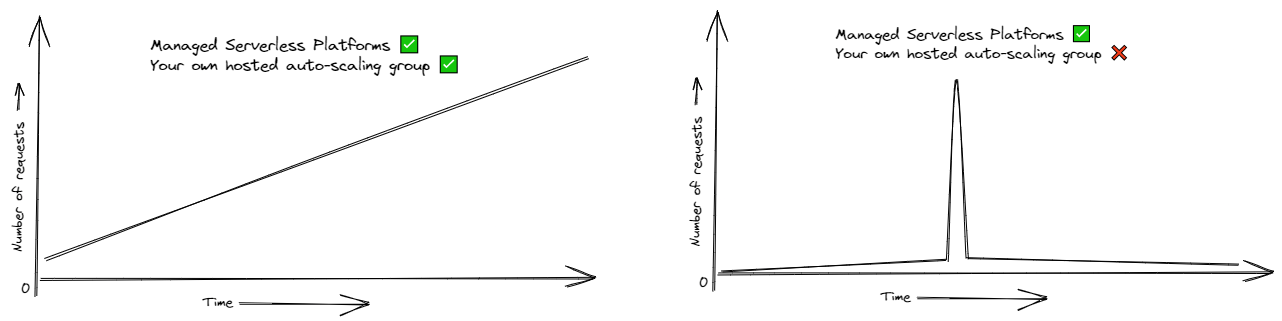

For us, auto-scaling groups with the right metrics triggering new VM Creation should be more than enough.

The downside is that it can’t handle spikes, say you’re receiving 100 requests per second on average with 2 instances and suddenly there are a million (Your startup just went viral from a TV Ad or a Promotional Campaign done well). No auto-scaling policy from any provider can ever handle that, providers can say “there’s infinite scaling” because they have enough idle-lying server capacity to handle even an unreasonable amount of requests coming in.

You would have to be smart about it and predict based on your business events when your auto-scaling policy has to be pre-triggered. Such times can include half an hour before flash sales, marketing events etc.

But if you have to do “load-prediction”, the whole point of serverless becomes irrelevant. In essence, serverless as a product is amazing, running a setup that mimics the capabilities of serverless ourselves is good enough till an event we did not predict happens.

If you don’t have to handle spikes, auto-scaling groups can work fine. Remember, it can handle surges and not spikes.

More from here

While this post covered a lot, we merely scratched the surface of the possibilities of serverless platforms and scaling.

Serverless platforms do a ton of other things apart from what we discussed:

- Logging of requests, memory, and compute usage + Any application logs that your function generates—This pushes scalability engineering to its limits, as for each invocation, thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of log lines are generated.

- Abstracting the process of building your function code. Most serverless platforms provide automated CI/CD pipelines that plug into your GitHub repositories which you can use to deploy your code without writing your own Dockerfiles and build pipelines.

- Error monitoring and logging for function crashes.

- Allowing functions to be invoked not just from the internet via an HTTP Request, but via integrations to Storage Buckets, VPC Events, Database events and Message Queues (The way auto-translates, auto-photo tagging on Google Photos etc work).

All the above, while basic requirements of any infrastructure platform, are extremely hard problems to get right.

And when it comes to managing containers on VMs and orchestrating them for efficient resource usage, there are better solutions like Kubernetes or Docker Swarm.

There’s never really an end to it. Remember, when it comes to serverless, it’s a multi-billion dollar industry with innovation at every corner and on every day. What I’ve mentioned in this post might be completely outdated when you’re reading this, and that’s a good thing.

With each iteration, these things get better and more efficient (Although more profitable for the big corps - but hey, they are here to solve our problems and make money doing it, so there’s nothing wrong with that).

Special thanks to Manish Kumar for reviewing this post, and Atishay Jain for providing his insights on scaling behaviour on the cloud.